Trade Routes and Emerging Colonial Economies

“What was the impact of trade routes on emerging colonies in the Americas?”

Good question and one that is often answered a bit too narrowly. The key issue is whether trade routes promoted resource extraction and/or economic development, and if the latter, what sort of development. Of course, the most famous route, with the greatest impact on New World colonies, was the Triangular Trade, which had some variants. In addition, though, there were several versions of a simpler two-way transatlantic trade, from the UK to the northern colonies, from France to Quebec, and from Spain/Portugal to Latin American places. Last, and less known, a transpacific trade took shape in the 17th century, connecting the Philippines with Mexico through the west coast port of Acapulco. So here we have at least half dozen routes to assess in terms of impacts.

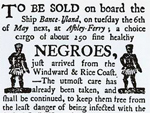

The core of the triangular trade, ca. 1600-1800, was the exchange of slaves for materials and goods – African captives brought to eastern Atlantic ports, exchanged for gold or British manufactured products, then transshipped brutally to colonial depots – Charleston, New Orleans, the Caribbean islands, and in smaller numbers, New York, for example. There, captives were again sold, for cash or goods (sugar, tobacco, timber) which returned to a UK starting point (often Liverpool). Yet this sequence was not the only one, particularly in New England, where merchants sent rum and other North American goods to Africa, secured slaves for auction to sugar plantations in the Caribbean, and brought liquid sugar (molasses) to American shores for distillation into more rum. Though this sounds tidy, actually, rarely was either triangle completed by one ship in one voyage; each triangle stands more as a mythical model than a description of standard practice. Nonetheless these ventures, plus those made by Spanish and Portuguese slavers extracted over nine million Africans from their home terrains across the 16th through the 19th centuries. That’s quite an impact, creating slave economies from Virginia to Trinidad to Brazil. Another three-sided trade involved slavery indirectly, as when Yankees sent colonial goods to the sugar islands, shipped to Russia to exchange sugar for iron, which returned to New England.

Bilateral trade is simpler to grasp, and yet may depart from our current notions of exchange. The Kingdom of Spain extracted precious metals from Latin America, sending back goods for colonizers, especially through Veracruz, which became Mexico’s principal east coast harbor. By contrast, French trade with Quebec was a constant drain on the monarchy’s funds; often goods sent to sustain some 50,000 settlers cost more than double the value of furs gathered and sold. However, Virginia tobacco sold to Britain at times created high profits, but this single-crop economy proved vulnerable to commodity price fluctuations (Cotton’s southern surge came after the American Revolution.). Clearly trade did not automatically translate into sustained development, though port cities did prosper, not least because they became anchors for coastal shipping within and among colonies. At times, expanding trade could irritate the colonizing state, as when Mexican merchants created a long-distance 16th-18th century trans-Pacific route from Acapulco, trading an estimated 100 tons of silver annually for Chinese silks, cottons, spices, and pottery – resources the Crown thought should be sent to Madrid instead. Overall, my sense is that colonial trade routes deepened exploitation of people and nature appreciably more than they fostered investment and economic development.

Bailey, Anne. African Voices of the Atlantic Slave Trade. Boston: Beacon, 2006.

Bjork, Katherine. “The Link That Kept the Philippines Spanish: Mexican Merchant Interests and the Manila Trade, 1571-1815.” Journal of World History 9 (1998): 25-50.

Bravo, Karen. “Exploring the Analogy between Modern Trafficking in Humans and the Transatlantic Slave Trade.” Boston University Int’nl Law Journal 25 (2007), 207-95.

Evans, Chris and Goran Ryden. Baltic Iron in the Atlantic World Leiden: Brill, 2007.

Hart, Michael. A Trading Nation: Canadian Trade Policy from Colonialism to Globalization. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2002.

Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation, Jamestown Settlement, and Yorktown Victory Center[VA]

Ostrander, Gilman. “The Making of the Transatlantic Slave Trade Myth,” William and Mary Quarterly 30 (1973): 635-44.

Rawley, James and Stephen Behrendt. “The Coastal Trade of the British North American Colonies,” Journal of Economic History 34 (1972): 783-810.

Canny, Nicholas. “Writing Atlantic History; or, Reconfiguring the History of Colonial British America,” Journal of American History 86 (1999): 1093-1114.

Price, Jacob and Paul Clemens. “A Revolution of Scale in Overseas Trade: British Firms in the Chesapeake Trade, 1675-1775.” Journal of Economic History 47(1987): 1-43.

Rawley, James and Stephen Berendt. The Transatlantic Slave Trade: A History. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005.

Oysters became a high-demand source of protein and nutrition following the Civil War. With the rise of industry and of shipping by rail, canneries and corporate oyster farming operations sprang up on both coasts, eager to supply the working class, and anyone else who wanted the tasty shellfish, with oysters shipped live or canned. In San Francisco, a center of oyster piracy, the boom years of the oyster industry corresponded, unsurprisingly, with those of the oyster industry—both took off in 1870, as the state began allowing major oyster farming operations to purchase the rights to underwater bay "land" (traditionally common property), and petered off in the 1920s, as silt and pollution disrupted the bay's ecosystem.

Oysters became a high-demand source of protein and nutrition following the Civil War. With the rise of industry and of shipping by rail, canneries and corporate oyster farming operations sprang up on both coasts, eager to supply the working class, and anyone else who wanted the tasty shellfish, with oysters shipped live or canned. In San Francisco, a center of oyster piracy, the boom years of the oyster industry corresponded, unsurprisingly, with those of the oyster industry—both took off in 1870, as the state began allowing major oyster farming operations to purchase the rights to underwater bay "land" (traditionally common property), and petered off in the 1920s, as silt and pollution disrupted the bay's ecosystem. At 15, Jack London bought a boat, the Razzle Dazzle, and joined the oyster pirates of San Francisco Bay to escape work as a child laborer. London wrote about his experiences in his semi-fictional autobiography, John Barleycorn, and used them in his early work, The Cruise of the Dazzler, and in his Tales of the Fish Patrol. The latter tells the story of oyster pirates from law enforcement's perspective—after sailing as an oyster pirate, London switched sides himself, to hunt his former compatriots.

At 15, Jack London bought a boat, the Razzle Dazzle, and joined the oyster pirates of San Francisco Bay to escape work as a child laborer. London wrote about his experiences in his semi-fictional autobiography, John Barleycorn, and used them in his early work, The Cruise of the Dazzler, and in his Tales of the Fish Patrol. The latter tells the story of oyster pirates from law enforcement's perspective—after sailing as an oyster pirate, London switched sides himself, to hunt his former compatriots. The working class romanticized oyster pirates as Robin-Hood-like heroes, fighting back against the new big businesses' private control of what had once been common land. Traditionally, underwater "real estate" was commonly owned—anyone with a boat or oyster tongs could fish or dredge without fear of trespassing. Following the Civil War, states began leasing maritime "land" out to private owners; and the public protested, by engaging in oyster piracy, supporting oyster pirates, scavenging in tidal flats and along the boundaries of maritime property, and, occasionally, engaging in armed uprisings.

The working class romanticized oyster pirates as Robin-Hood-like heroes, fighting back against the new big businesses' private control of what had once been common land. Traditionally, underwater "real estate" was commonly owned—anyone with a boat or oyster tongs could fish or dredge without fear of trespassing. Following the Civil War, states began leasing maritime "land" out to private owners; and the public protested, by engaging in oyster piracy, supporting oyster pirates, scavenging in tidal flats and along the boundaries of maritime property, and, occasionally, engaging in armed uprisings.  The opera satirized Governor William Evelyn Cameron's second raid against oyster pirates in the Chesapeake Bay, on February 27, 1883. Cameron had conducted a very successful raid the previous February, capturing seven boats and 46 dredgers, later pardoning most of them to appease public opinion—which saw the pirates as remorseful, hard-working family men. His second raid, in 1883, went poorly. Almost all of the ships he and his crews chased escaped into Maryland waters, including the Dancing Molly, a sloop manned only by its captain's wife and two daughters (the men had been ashore when the governor started pursuit). The public hailed the pirates as heroes and ridiculed the governor in the popular media—the Lynchberg Advance, for instance, ran a

The opera satirized Governor William Evelyn Cameron's second raid against oyster pirates in the Chesapeake Bay, on February 27, 1883. Cameron had conducted a very successful raid the previous February, capturing seven boats and 46 dredgers, later pardoning most of them to appease public opinion—which saw the pirates as remorseful, hard-working family men. His second raid, in 1883, went poorly. Almost all of the ships he and his crews chased escaped into Maryland waters, including the Dancing Molly, a sloop manned only by its captain's wife and two daughters (the men had been ashore when the governor started pursuit). The public hailed the pirates as heroes and ridiculed the governor in the popular media—the Lynchberg Advance, for instance, ran a  Oyster piracy highlights the class tensions that sprang up during post-Civil War industrialization. Big business and private ownership began to drive the economy, shaping the lives of the working class and changing long-established institutions and daily patterns. Young people such as Jack London turned to oyster piracy as an escape from the new factory work—and the working class chaffed against the loss of traditional maritime common lands to business owners.

Oyster piracy highlights the class tensions that sprang up during post-Civil War industrialization. Big business and private ownership began to drive the economy, shaping the lives of the working class and changing long-established institutions and daily patterns. Young people such as Jack London turned to oyster piracy as an escape from the new factory work—and the working class chaffed against the loss of traditional maritime common lands to business owners.