Animating the Home Front

I am looking for an electronic copy of a cartoon which shows most of the different aspects of the home front effort in America during World War II.

America’s home front effort included recruiting for the military, participating in scrap drives, paying income taxes, buying war bonds, using rationing coupons, planting Victory gardens, encouraging sanitation, volunteering for civil defense work, increasing public morale, and participating in industrial retooling and production. The Hollywood studios that were making cartoons at the beginning of the war were quickly drafted into turning their art to the war effort, to mobilize the American public. Cartoons were just one part of a propaganda effort, which also included the production and distribution of feature films, posters, war-themed commercial radio, newspaper and magazine advertising, the organization of celebrity tours and war bond drives, the establishment of censorship offices, and the formulation and distribution of a barrage of information and directives from various government officials and agencies.

Leon Schlesinger Productions produced popular cartoons featuring Daffy Duck and Bugs Bunny for Warner Brothers Studios, many of which had war themes, such as “The Ducktators” (1942), “Confusions of a Nutzy Spy” (1943), “The Fifth Column Mouse” (1943), “Tokio Jokio” (1943), “Daffy—The Commando” (1943), “Falling Hare” (1943), and “Draftee Daffy” (1945).

At least two of these Warner Brothers’ cartoons focused on home front activities and might be the cartoon you’re thinking of: “Scrap Happy Daffy” (1943), and ”Wacky Blackout” (1942).

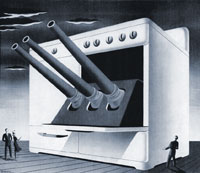

Walt Disney also produced many war-themed cartoons with Mickey, Donald, Goofy and the rest of the gang, some of which were focused on the home front, such as “Out of the Frying Pan into The Firing Line” (1942), and ”Food Will Win the War” (1942).

A collection of short cartoons and movies from the Disney Studio during World War II, which includes many intended for the home front, was released (for purchase) in 2004 as a 2-disc DVD, “On the Front Lines,” in the series “Walt Disney Treasures.” This collection includes such titles as “Donald Gets Drafted” (1942), “Private Pluto” (1943), “Home Defense” (1943), “All Together” (1942), “Defense Against Invasion” (1943), and “Cleanliness Brings Health” (1945), as well as many others. The collection also includes Disney’s 1943 animated film, “Victory Through Air Power,” as well as a few of the hundreds of training films that the Disney studio made for the War Department or the National Film Board of Canada, such as “Four Methods of Flush Riveting” (1942).

Clayton R. Koppes and Gregory D. Black, Hollywood Goes to War: How Politics, Profits and Propaganda Shaped World War II Movies. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990.

Thomas Doherty, Projections of War: Hollywood, American Culture, and World War II. New York: Columbia University Press, 1999.

James J. Kimble, Mobilizing the Home Front. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2006.

Steven Watts, The Magic Kingdom: Walt Disney and the American Way of Life. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1997.

Cass Warner-Sperling, Cork Millner, and Jack Warner. Hollywood Be Thy Name: The Warner Brothers Story. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 1999.