A review of the secondary literature on the Burr-Hamilton duel does indeed reveal some inconsistency on whether the duel was illegal. Perhaps the inconsistency is partly the result of conflicting personal and political judgments contemporary to the event: Burr and Hamilton were leaders of opposing political factions.

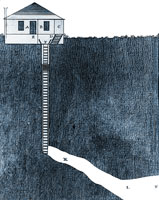

The duel was fought on the early morning of July 11, 1804. Burr and Hamilton, and their seconds, had rowed out separately from New York City across the Hudson River to a narrow spot just below the Palisades at Weehawken, New Jersey. It was a secluded grassy ledge, only about six feet wide and thirty feet long above the river, with no footpath or road leading to it. Cedar trees growing on the ledge partially obscured it from across the river.

It was a place where duelists from New York City could go to settle their affairs in secret as dueling per se was not illegal in New Jersey. Duels took place at the Weehawken spot from about 1799 to 1837, when the last determined pair of duelists were interrupted in their preparations by a police constable, who put them in jail to await the action of the grand jury.

Hamilton’s 18-year-old son Philip had been killed in a duel there on January 10, 1802, just two years previously. After that, Hamilton had successfully helped pass a New York law making it illegal to send or accept a challenge to a duel. Those convicted were liable to lose the right to vote and were barred from holding public office for 20 years, but no duelist had yet been prosecuted. Public sentiment supporting the duty to uphold one’s honor if it had been questioned was still strong and could not easily be ignored, even by those who questioned the practice of dueling.

The participants in a duel—including the principals and their seconds—also typically arranged things in order to make it difficult to convict them. For example, they ensured that none of the participants actually saw the guns as they were being transported to the dueling ground, they kept silent about their purpose, and they had the seconds turn their backs while the shots were exchanged. This would allow them to later deny having heard or seen specific things, decreasing the chance that they might be held as accessories to a crime.

After the duel, Burr and Hamilton were each transported back across the river by their seconds, Burr having mortally wounded Hamilton, who died at his physician’s home the following day.

Burr was apparently surprised at the public outrage over the affair

In New York City, a coroner’s jury of inquest was called on the 13th of July, the day after Hamilton’s death. Although Hamilton was shot in New Jersey, he died in New York, and therefore, Burr (his enemies said) could be prosecuted in New York. The jury sat intermittently until August 2, and considered, among other evidence, the contents of the letters that Hamilton and Burr had exchanged before the duel. These letters suggested to some on the jury that Burr had in fact enticed or even forced Hamilton into the duel, pushing the affair over the line from one of settling honor to one of deliberate murder which was a capital offense.

The coroner’s jury returned a verdict that Burr had murdered Hamilton, and that Burr’s seconds were accessories to the murder. New York then indicted Burr not only for the misdemeanor of “challenging to a duel,” but also for the felony of murder.

In November, Burr was also indicted for murder—which is to say, not for dueling—by a grand jury in Bergen County, New Jersey, because the duel had taken place there.

After the duel, Burr was apparently surprised at the public outrage over the affair. Fearing imminent arrest, he fled to New Jersey, then to Philadelphia, and then to Georgia.

He wrote to his daughter Theodosia: "There is a contention of a singular nature between the two States of New York and New Jersey. The subject in dispute is, which shall have the honor of hanging the Vice-President. You shall have due notice of time and place. Whenever it may be, you may rely on a great concourse of company, much gayety, and many rare sights."

He was still the Vice President, however, and he determined to go back to Washington to act as President of the Senate during its upcoming session and preside over the debate and vote concerning the impeachment of Supreme Court justice Samuel Chase. The impeachment proceedings were part of a partisan struggle between Jeffersonian Republicans and Federalists, and Burr might be expected to influence the outcome if he were allowed to preside over the Senate. A large group of Congressmen signed a letter to New Jersey Governor Joseph Bloomfield describing the Hamilton-Burr affair as a fair duel and asking him to urge the Bergen County prosecutor to enter a nolle prosequi in the case of the indictment, in other words, to drop the case. This is what eventually happened.

The murder charge in New York was eventually dropped as well, but Burr was convicted of the misdemeanor dueling charge, which meant that he could neither vote, practice law, nor occupy a public office for 20 years.