Rethinking "Westward Expansion": A Guide for Preservice Teachers

What is it?

“Westward expansion” is a topic covered in many U.S. history textbooks and one that appears in most every state's social studies standards. At the same time, most states also mandate that students be taught to consider history from multiple perspectives or points of view. But what does it mean to consider multiple perspectives about westward expansion? What would it mean to consider the point of view of Native Americans who were the most directly affected by the process called western expansion? A change of perspective might reveal a great deal. As historian Daniel Richter notes in his book, Facing East From Indian Country, “if we shift our perspective to try to view the past in a way that faces east from Indian country, history takes on a very different appearance.” Historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz makes a similar point in her 2015 An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States, “Writing US history from an Indigenous peoples' perspective requires rethinking the consensual national narrative. That narrative is wrong or deficient, not in its facts, dates, or details but rather in its essence. Inherent in the myth we've been taught is an embrace of settler colonialism and genocide.” This guide provides teachers with resources to analyze Library of Congress primary sources so that students can account for Indigenous perspectives that “faced east” in their analysis of westward expansion, colonialism, and land rights.

Key points:

- The activity outlined here will take one 90-minute period or two 45-minute periods. It is appropriate for a high school U.S. history classroom, but can be modified for a variety of learners.

- Students will analyze, interpret, and evaluate primary sources.

- Students will learn about Native peoples responses to the settlement of the western U.S. and gain new perspectives to better understand "Westward Expansion".

Approach to Topic

Even the term “westward expansion” assumes a facing-west point of view rather than a perspective of someone already living in the west. While U.S. history textbooks now include more topics related to Native people, these topics are typically presented as a subset of a larger story about westward expansion. For example, in McGraw Hill’s United States History and Geography, the chapter on westward expansion, “Settling the West,” contains a section titled “Native Americans”, but it comes after two other sections: “Miners and Ranchers” covering the California gold rush and cattle ranching in the west, and “Farming the Plains” which deals with white settlers seeking farmland in the west. Framing and organizing the topic this way presents Native people as obstacles or complications to the westward movement of settlers. This framing also implies that westward expansion was more or less inevitable rather than a series of deliberate choices, an idea often closely linked with the concept of “manifest destiny” as a divinely-ordained establishment of the United States.

The textbook narrative obscures the fact that the taking of Native people’s land was an intentional project backed by the U.S. federal government. Instead of emphasizing the deliberate dispossession of Native land, students usually read about a series of general breakdowns in relations between two groups, settlers and Native people. For example, the 1867 Indian Peace Commission is presented under a subheading of “Doomed Plan for Peace” while the 1887 Dawes Act is presented as a largely positive plan to help Native Americans that simply “failed to achieve its goals.” In other places the purposeful destruction of Native resources is described in the passive voice, such as “The buffalo were rapidly disappearing.” In response to these textbook depictions, teachers can encourage students to analyze how these topics are framed in their textbooks and think about how they might look from another point of view.

To teach students to consider the multiple perspectives on westward expansion, it is also important for teachers to think critically about their own relationship to place and support their students in doing the same. The history of “westward expansion” involved a series of events where Native people were displaced, removed from their land, and coerced into signing disadvantageous treaties many of which were later broken by federal, state, or territorial governments. As scholars Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang have written:

In order for the settlers to make a place their home, they must destroy and disappear the Indigenous peoples that live there. Indigenous peoples are those who have creation stories, not colonization stories, about how we/they came to be in a particular place - indeed how we/they came to be a place . . . For the settlers, Indigenous peoples are in the way and, in the destruction of Indigenous peoples, Indigenous communities, and over time and through law and policy, Indigenous peoples’ claims to land under settler regimes, land is recast as property and as a resource. Indigenous peoples must be erased, must be made into ghosts.

In teaching this topic to students, it is therefore necessary to not make Native people into the “ghosts” that Tuck and Yang reference and to understand that Native people did not disappear, indeed they refused to, despite the repeated efforts of governments and settlers.

One challenge to including the perspective of Native people at this time is that colonial record-keeping disproportionately documented the perspectives of white men in positions of social authority this is part of the same disappearing process described by Tuck and Yang. Though the sources are sometimes more difficult to locate, resources do exist to help teachers actively include the perspectives of Native people and share it with students. Many Native people throughout the past and up to the present day have continued to assert their points of view in spaces visible to the wider U.S. public. Their voices are sometimes visible within colonial sources, including through a process of reading against the grain. Indigenous people have vigorously defended against settler land theft and continue to invest in their cultural, governmental, artistic, linguistic, and social systems today, despite centuries of colonial disruptions.

This guide will focus on two examples of Indigenous people who advocated for Indigenous rights in the early 1900s: Zitkala-Ša (also known as Gertrude Simmons Bonnin) and Charles Eastman (also known as Ohiyesa). Both were important figures in the Society of American Indians, an organization established by Native intellectuals from across the country in 1911. The members of the SAI, in scholar Philip J. Deloria’s words, “worked actively to preserve elements of Native cultures and societies from destruction.” Through their words and actions teachers can locate an alternative to the westward expansion point of view and make a different history more apparent.

Description

Zitkála-Šá

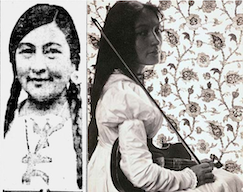

Zitkála-Šá (pronounced Zeet-KA-la-sha) was Yankton Dakota, born on the Yankton Indian Reservation in South Dakota in 1876. Like many thousands of Native children at the time was also forced to attend a boarding school far away from her home. At eight years old, Zitkála-Šá left Yankton and her family to attend the Indiana Manual Labor Institute in Wabash, Indiana over 700 miles away. At the institute she was given the name Gertrude Simmons (later Gertrude Simmons Bonnin) which she also used at various points in her life. Zitkála-Šá would attend the boarding school for three years and there learned to play violin and piano. She returned to Yankton, and then went back to the institute three years later. Upon graduation, she took a position as a music teacher at the school. Zitkála-Šá/Gertrude Simmons became an expert at navigating two cultures. Some scholars have seen Zitkála-Šá as a person who assimilated into white-U.S. culture, but more recently scholars have emphasized how she used these cultural skills to support and defend Native people and culture. As historian Tadeusz Lewandowski writes in his biography of Zitkála-Šá, she “fought the dispossession of Indians with every tool of white society she had mastered.”

In her life, Zitkála-Šá rose to prominence as a musician, writer, and political advocate. An accomplished violinist, she performed at the White House for President William McKinley in 1900 and as a soloist at the Paris Exposition that same year. A prolific writer, Zitkála-Šá’s presented depictions of American Indians that emphasized family and community in books such as American Indian Stories and presented her own experiences in personal essays for Harper’s Monthly and The Atlantic Monthly.

In perhaps her most famous work, The Sun Dance, Zitkála-Šá translated the sacred, ceremonial dances performed by various Native groups across the Americas - dances that had been declared illegal by the federal government - into an opera. Working with composer William F. Hanson, Zitkála-Šá used her training in western music and her knowledge of Native culture to demonstrate the beauty of these dances in a form that would draw the attention of the larger U.S. public.

For more background on how The Sun Dance opera came to be written by Zitkála-Šá and Hanson have students listen to an excerpt from this interview with Zitkála-Šá P. Jane Hafen from the podcast Unsung History https://www.unsunghistorypodcast.com/zitkala-sa/. The excerpt on The Sun Dance is from 21:16 to 25:53.

Questions to ask about this source: In what ways was The Sun Dance a product of western culture and in what ways was it a product of Native American culture? How does it demonstrate Zitkála-Šá’s understanding of two cultural worlds?

Zitkála-Šá also used her cultural expertise to lobby the government directly on policies that affected Indigenous people and in particular advocated for the government to protect Native people and culture.

Primary Source #1

“She is Watching Congress,” Evening Public Ledger, February 22, 1921 https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045211/1921-02-22/ed-1/seq-20/

Primary Source #2

“Sioux Princess Closely Watches Indian Welfare,” The Richmond Palladium and Sun-Telegram, February 26, 1921 https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn86058226/1921-02-26/ed-1/seq-15/

Questions to ask about these primary sources:

- Although white reporters regularly used stereotypical and condescending terms to refer to Zitkála-Šá (i.e. describing her as a “Sioux princess” who was “watching Congress”), she chose to present herself in traditional Native clothing. What might have been her reasons for this choice?

- How might this decision have fit with her goals to influence Congress on Native issues?

- Compare these photos to a photo of Zitkála-Šá in western clothing: https://www.nps.gov/people/zitkala-sa.htm

- Why might she choose one form of dress over another depending on the situation?

- How might her choice of clothing affected how audiences viewed her?

- How might her choice of clothing made it more likely for white audiences to listen to her?

Along with other members of the Society of American Indians, Zitkála-Šá advocated for Native Americans to receive the full benefits of United States citizenship including the right to vote. Scholar K. Tsianina Lomawaima argues that the Society for American Indians saw citizenship as a tool to defend Native people from dispossession and protect their land. The Dawes Act, also known as the General Allotment Act of 1887, converted Indigenous territories from collective management and converted that territory to private, transferrable land deeds for individual land tracts based on western land ownership. As a result of the Dawes Act, Indigenous people lost 90 million acres of land in less than fifty years.

Under the Dawes Act, Native people whom the US government did not see as “competent” had their land (called an “allotment”) held by the US government. Though Native people were already citizens of their Native nations and did not necessarily want US citizenship, Zitkála-Šá saw U.S. citizenship as one possible form of protection against land loss. She not only advocated for citizenship for Native Americans but also for women to receive the right to vote. In this source from 1918, Zitkála-Šá addressed the National American Women's Suffrage Association and tied together the causes of the women’s vote and the vote for Native Americans:

Primary Source #3:

Maryland Suffrage News, June 15, 1918

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn89060379/1918-06-15/ed-1/seq-5/

Question to ask about this primary source:

- Why might Zitkála-Šá have decided to speak to the National American Women's Suffrage Association?

- What were her goals? [For more resources on Native American women advocating for womens’ suffrage, see the guide on Native Women and Suffrage]

In 1924, partially as a result of the lobbying of Zitkála-Šá and the Society of American Indians, the Indian Citizenship Act was passed. This concluded the process of making all Native people born in the United States citizens. Although it is important to note that states could restrict the Native people’s right to vote and states such as Utah and New Mexico did just that. Zitkála-Šá continued to speak out on Native issues to both national and local groups. For example, in 1928 in Bismarck, North Dakota she gave a talk on the history of Native people and the current Native issues to the Rotarians, a community-based organization.

Primary Source #4:

“Rotarians Hear Famous Woman at Weekly Meeting,” The Bismarck Tribune, June 14, 1928. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85042243/1928-06-14/ed-1/seq-7/

Questions to ask about this primary source:

- According to the newspaper article, what did Zitkála-Šá tell the Rotations about the history of Native people?

- Why do you think the article addresses Indigenous participation in the World War?

- What did she say about the current situation faced by Native people?

- Why do you think she chose to emphasize these issues?

Charles Eastman

As was the case with Zitkála-Šá, Charles Eastman’s upbringing involved direct experience with white society, his Dakota nation, and a variety intertribal communities. He too developed skills to move within and between these social spaces. Born in 1858 near Redwood Falls, Minnesota to a Dakota woman named Winona who died in childbirth, he was given the name “Hakadah.” He fled with his family to Canada following the U.S.-Dakota War of 1862. As an older child, he was given the name Ohiyesa (pronounced oh-he-yes-suh and meaning “the winner”) after a victory in a lacrosse match. When he was 15, his father — who had been estranged from the family — returned and demanded that Ohiyesa live with him in Dakota Territory near present day Sioux Falls, South Dakota. Ohiyesa’s father had converted to Christianity and taken the name “Jacob Eastman”. His father changed Ohiyesa’s name to “Charles Alexander Eastman” and enrolled him in white schools. Similar to Zitkála-Šá, Eastman grieved about the separation from the culture he was born into while, at the same time, he also excelled in his new environment. After secondary school, he attended college at Beloit College and then Dartmouth, and eventually earned his degree in medicine from Boston Medical School in 1890.

Eastman sought to use his training to help Native people so shortly after earning his degree, he accepted a position on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. On December 29, 1890, only a few weeks after Eastman’s arrival, 500 soldiers of the United States 7th Cavalry confronted a band of 350 Miniconjou Lakota Indians that included women and children and fired on the unarmed group killing more than 150 people. It is important to emphasize that this incident, which would become known as the Wounded Knee Massacre was not an isolated incident but part of a pattern where U.S. military forces, often commanded by officers with little to no knowledge of Native people and irrationally paranoid about their safety fired on defenseless Native groups that included unarmed men, women, and children with deadly results. Soldiers and travelers took souvenirs and graphic photographs document the carnage. At Pine Ridge, Eastman helped treat the few who survived. For more on the Wounded Knee Massacre read this entry from the Encyclopedia of the Great Plains: http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.war.056

In addition to his career as a physician, Eastman wrote about Native American people and culture in a way that both defied the stereotypes prevalent among whites at the time and also countered the prevailing notion that Native Americans were a disappearing people and culture. In this account, Eastman related a visit to the Objibwe of Northern Minnesota.

Primary Source #5:

As I approached the island next morning. I saw a pretty procession of birch-bark canoes converging upon it. This was evidently a gathering of the clans whose highway is the blue water, and the graceful canoe their sole means of transportation. Invariably the man sits in the bow of the light craft, his wife at the stern, and the children by pairs between so low that only the tops of their black heads are visible. All the household effects are carried, except the dogs, who are obliged to run along the shore and swim the narrows from island to island.

The whole family, even little children, paddle the canoe, and such skill, confidence and safety I have never seen elsewhere. "When the wind rises and the water is so rough that no one can be found willing to venture out in launch or row boat, these people may be seen skimming the big waves like aquatic birds. Along the shore I saw women here and there, setting their gillnets for the wily pike and bass. Most of them do this as an every-day duty. In camp, some were making nets, others working upon their birchen cones, preparing the bark and the cedar bindings, or soaking the strappings and boiling pitch to glue the seams.

Majigabo's immediate village was the meeting-place, and there was the "sacred ground" where they initiate new members into their lodge, consecrate some of the children, celebrate old rites, and commemorate the departed. There were feasts galore of the delicious wild rice, venison, dried moose meat, bear steaks, and sturgeon. Maple sugar packed in small birchen boxes called "mococks" was plentiful and of the finest flavor. Here is one chief just beyond sight of the smoke of the locomotive, in the heart of a wilderness already penetrated by the whistle of the saw-mill, who still preserves many of the ancient usages of his forefathers.

Charles Eastman, “My Canoe Trip Among the Northern Ojibwe Indians of Minnesota The Oglala light. [volume], May 01, 1911. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/2017270500/1911-05-01/ed-1/seq-13/

Questions to ask about this primary source:

- What year did Eastman write this account?

- In what ways does the account reveal the persistence of Indigenous intellectual traditions and technologies despite colonial pressures to assimilate?

- How does this reshape the narrative about westward expansion present in your textbook?

- In what ways did Eastman emphasize family, community, and land relations in his description? Why do you think he did that?

In the Classroom

The primary sources above can be incorporated into a unit that also covers westward expansion. Teachers can use this opportunity to have students reflect on how the term “westward expansion” only considers some perspective while leaving others out — namely the perspectives of those in the “west” who are “facing east”.

In the classroom, students can be prompted to reflect on these east-facing perspectives:

- In a 5 minute think-pair-share activity, students can think of their own response, talk it through with a partner, and then “share out”.

- Then students can be asked how they could learn about the missing points of view - what kind of evidence or sources might provide these perspectives? Again students can come up with ideas in another 5 minute think-pair-share activity.

- The class can then transition into analyzing the primary sources included in this guide. Communicate to students that this is one way to consider multiple points of view. Referencing their list of other points of view to consider and what evidence might be used, teachers can and should acknowledge that not all points of view are being considered nor will they be able to analyze and consider all of the evidence, but the sources they will examine do provide a valuable perspective that is not present in most textbooks.

- Put the students in groups of 3-4 and give them a selection of 2-3 sources.

- As the students examine the sources, prompt them with the guiding questions included above with each primary source. For more scaffolding, teachers may have students fill out primary source analysis sheets for one or more of the sources: https://www.loc.gov/programs/teachers/getting-started-with-primary-sources/guides/

- After examining the sources, ask the students to discuss in their groups: What issues related to Native people were Charles Eastman and Zitkála-Šá most concerned with? What perspective do these sources provide on westward expansion? How does the term “westward expansion” hide other perspectives, namely the struggle of Indigenous people over their homelands and livelihood? What would an east facing version of this story look like?

Extension/enrichment ideas: Students could research further into the history of the Society of American Indians or any of its prominent members such as Rev. Sherman Coolidge, Arthur C. Parker, Angel DeCora, Francis LaFlesche, or Marie Bottineau Baldwin. Using this research students could then develop a multimedia digital project that presents a “facing east” history of westward expansion. As part of this project students should reflect on what they would want to communicate about this point of view, to show that “westward expansion” was not inevitable and to show how Native people persisted and refused to simply disappear. Primary sources like those above and others from the Library of Congress could be featured in a website or slide presentation. As part of the project, students might also research the history of their own communities and the Native people who lived there in the past and live there in the present.

Teaching history inevitably means teaching about topics that generate strong reactions from a wide range of people. While not every reaction can be anticipated, the following tips can provide a strong basis for a rationale for your learning activities:

General Tips for Teaching Controversial Subjects

- Center activities on primary sources. Primary sources are tangible evidence that allow students to engage directly with history. These primary sources in particular were preserved and digitized by the Library of Congress because they were deemed important to the history of the United States.

- Discussion and analysis of these sources can be wide ranging, but within each class those discussions can always be turned back to the source itself.

- The sources are also, by definition, only pieces of a puzzle. They bring us closer to understanding the past but there is always room for doubt and uncertainty.

- Questions, Observations, and Reflections should come from students. These are primarily student-directed learning activities. It is the instructor's role to create a space for inquiry and empower students to drive the inquiry.

- It may help to remind students at the outset that it is normal for different individuals to come to different conclusions, even when we are looking at the same sources. Further, it would be strange if we all agreed completely on our interpretations. This can normalize the strong reactions that can come up and enables educators to discuss the goal of historical research, which is to hopefully go beyond the realm of individual perspective to access a fuller understanding of the past that takes multiple perspectives into account.

- Teaching historical topics that involve violence and other trauma can be traumatic for some students as well. Providing students with previews of what content will be covered and space to process their emotions can be helpful. The following video series from the University of Minnesota contains further tips for teaching potentially traumatic topics: https://extension.umn.edu/trauma-and-healing/historical-trauma-and-cultural-healing.

Additional Readings/Viewings

Sabzalian, Leilani. Indigenous Children’s Survivance in Public Schools.

“Stories I Didn’t Know,” Rita Davern and Melody Gilbert dir. https://www.storiesididntknow.com/

Christine Sleeter, Critical Family History, https://www.christinesleeter.org/critical-family-history

Zitkala-Ša, “Why I am a Pagan,” The Atlantic, 1902. https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1902/12/why-i-am-a-pagan/637906/

“Zitkala-Ša”, Nation of Writers Podcast, Interview with scholar P. Jane Hafen,

https://americanwritersmuseum.org/podcast/episode-13-zitkala-sa/

“Zitkala-Ša”, Unsung History Podcast, Interview with scholar P. Jane Hafen

https://www.unsunghistorypodcast.com/zitkala-sa/

On the history of the Dawes Act: Indian Land Tenure Foundation, https://iltf.org/land-issues/history/

Ohiyesa: The Soul of an Indian dir. Std Beane https://visionmakermedia.org/ohiyesa/

Documentary made by Eastman’s descendents

Kiera Vigil, Indigenous Intellectuals: Sovereignty, Citizenship, and the American Imagination, 1880-1930, Cambridge University Press, 2018

Dr. Vigil discusses her book on the podcast here: https://newbooksnetwork.com/kiara-m-vigil-indigenous-intellectuals-sovereignty-citizenship-and-the-american-imagination-1880-1930-cambridge-up-2018