"Teachers," the Greek writer Nikos Kazantzakis wrote, "are those who use themselves as bridges, over which they invite their students to cross; then having facilitated their crossing, joyfully collapse, encouraging them to create bridges of their own." With Kazantzakis’s maxim under my wing, I have nurtured his approach to teaching history for 30 years. Washington, DC, and its environs is the great laboratory of democracy. Given the chance to teach in the Washington, DC, area, I can empower my students with a special kind of learning—one infused by time, place, and space.

Rationale

The Individualized Field Trip (IFT) permits students to encounter the past at historic sites and museums, all within the context of learning history based on state and national standards. They make outstanding summative assessment tools, while at the same time permitting students to have an enjoyable and fun experience while they learn.

Description

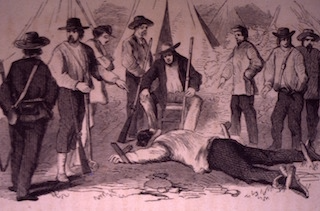

The IFTs I have constructed over the last two decades have included student visits to battlefields, cemeteries, public monuments, history and art museums, and other historic sites. These activities are designed to have students, on their own time, visit these places, not simply for extra credit but for required enrichment of my classes. In each case students carry worksheets, a camera, and sometimes readings that they are to complete while visiting their particular site. These trips become a record of their experience, be they studying George Washington, while visiting Mount Vernon; Theodore Roosevelt while viewing an artistic exhibition interpreting his life at the National Museum of American Art; walking the National Mall and looking at the 20th-century war memorials to World War II, and the Korean and Vietnam Wars; or traipsing through Congressional Cemetery in search of the final resting places of Mathew Brady, the famous Civil War photographer, or feminist sculptor Adelaide Johnson, whose National Memorial to the Women’s Rights Movement sits in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol.

These activities are designed to have students, on their own time, visit these places, not simply for extra credit but for required enrichment of my classes.

In the days before PowerPoint I used to have students create photo essays, placing images on poster board and adding captions underneath each image for identification. Today with more sophisticated technology and access to digital archives via the web, students can now craft engaging PowerPoint presentations that incorporate not only the pictures that they take at these sites, but archival images as well.

Tailoring IFT to Teaching Unit

In my regular U.S. History classes I generally require IFTs for three of our four quarters. The IFT for the first quarter is connected to the Colonial Era, Revolutionary Era, and Early American Republic by visiting Mount Vernon. In the second quarter, students visit the National Gallery of Art and study the 1900 plaster cast of sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s Robert Gould Shaw and 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Memorial. They also visit the National Memorial to African American Soldiers and Sailor’s Memorial by Ed Hamilton dedicated in 1997 which sits a short distance from Howard University, the first institution of higher learning for blacks created during Reconstruction. These visits are related to our study of the American Civil War. During the last quarter students are assigned an IFT I call “Echoes from the Mall,” which requires that they study the three memorials on the National Mall, all erected since 1982, that honor American sacrifice during those conflicts.

Historic Sites as Classrooms

In all of these instances students complete worksheets (Mount Vernon, National Portrait Gallery, Civil War sculpture, and monuments along the Mall) I designed during the groundwork stage of the activity, where I pre-visit the site. The worksheets are specific and can only be answered by visiting the site. Students also must take at least two photographs of the sites during their visit. These photographs eventually illustrate journal entries that students complete, and are placed in their bound composition books. They are also used to decorate a section of my classroom called Clio’s Corner, where images of these student-historians at work are placed on display. To explore the worksheets for each of these trips, see the “download” part of this entry.

Does This Only Work in DC?

While it is true that I may live near Washington, DC, and have access to all these incredible places, I remind you that history and memory have taken place all across the nation. Working with local historical societies, small house museums, and even public libraries can go far in offering you and your students a singularly unique view of the past. Local history can work as a prism for larger issues in American history, connecting your town or community to the bigger picture.

My biggest suggestion is to encourage you to do your homework before you send the students on their mission—you need to visit these places yourself.

My biggest suggestion is to encourage you to do your homework before you send the students on their mission—you need to visit these places yourself. That is crucial in crafting these activities. You need to know what you want your students to see, feel, and experience.