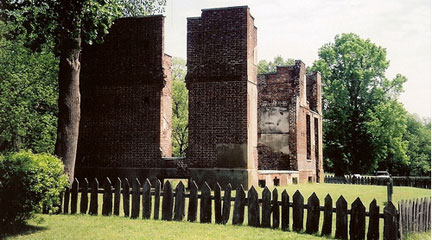

Fort Mims

Fort Mims site commemorates the Fort Mims battle which took place August 30, 1813. The attack on Fort Mims is considered a leading cause of the Creek War of 1813-1814.

Site offers no staff or facilities, according to website.

Fort Mims site commemorates the Fort Mims battle which took place August 30, 1813. The attack on Fort Mims is considered a leading cause of the Creek War of 1813-1814.

Site offers no staff or facilities, according to website.

Located nine miles north of Tappen, this is the approximate location of a campsite used by the 1863 Sibley expedition following the Battle of Big Mound. There is a grave marker on the site.

Minimal information about site, without any indication whether site includes any interpretation/docent services.

Fort Clark Trading Post State Historic Site is one of the most important archaeological sites in the state because of its well-preserved record of the fur trade and of personal tragedy. More than 150 years ago, it was the scene of devastating smallpox and cholera epidemics that decimated most of the inhabitants of a Mandan and later an Arikara Indian village. The archaeological remains of the large earthlodge village, cemetery, and two fur trade posts (Fort Clark Trading Post and Primeau's Post) are protected at the site, located one and one-quarter mile west of the town of Fort Clark, Mercer County.

Site may not offer any interpretative services beyond a self-guided tour and signage.

High above the Missouri and Osage rivers, visitors to Clark's Hill/Norton State Historic Site can absorb the intriguing history of the hill, which will take them back to the epic journey of captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. On June 13, 1804, they camped at the base of what is now known as Clark's Hill.

The site offers a hiking trail with interpretative signs.

Why were Indians in South America able to create great civilization, and those in present USA and Canada weren't?

I’m not sure how this question defines “great civilization,” but it seems that, like most other people educated in the United States, the questioner is unaware of the highly stratified, centralized, and elaborate societies that did exist north of the Rio Grande prior to the arrival of Europeans. We are taught that Indian societies in North America had no governments, class structures, religions, intellectual traditions, or other elements of what Western European philosophy calls “civilization.” But to contrast that view, I'll offer a few examples. I think we can fairly say that all societies, regardless of how elaborate their social and political structures may be, are “civilized.” The largest city in North America prior to 1492 was called Cahokia, located on what is today the Missouri River across from St. Louis. As a city-state, the population of 15,000 people was comparable to London or Paris at that time. Cahokia was the center of an elaborate trade network that stretched across the entire continent from 950 to 1250 AD. City residents, along with laborers from far away, traveled to Cahokia over the course of several hundred years to build enormous earthen mounds. The largest one is 15 acres around and is the largest earthen structure in the Western Hemisphere. These mounds—not unlike European cathedrals in spiritual or architectural significance—served as symbols of power for elite religious and political leaders. These leaders often lived atop the mounds to be closer to the sun, their spiritual source of power. The influence these leaders possessed was enormous. Not only could they command the construction of mounds, but they held the reins of the city's economic and military fortunes as well. Because of the extent of Cahokia's trade networks, the consequences of their decisions were felt all over the continent.

Another immense center of trade and spiritual power was located in Chaco Canyon in what is now New Mexico. Inhabitants and visitors to the canyon built 12 structures between 900 and 1150 AD, which had 200 or more contiguous, multistoried rooms and numerous “kivas,” or round, windowless areas that today the Hopi and Pubelo Indians (descendants of the people who built Chaco) use for worship. Like Cahokia, the labor required to build such structures must have been enormous and well-coordinated, evincing a sophisticated political, economic, scientific, and social organization. Surrounding these 12 structures were between 200 and 350 villages in the canyon. An estimated 15,000 people inhabited the area. Among archaeologists, two theories are popular about why Chaco was built. The first centers on trade and exchange. Archaeologists have found items from Mexico and Central America in towns and villages up to 60 miles away from the central part of the canyon, along with a system of roads. This evidence leads them to speculate that the Chaco structures were the center of trade, where people bought and sold goods. The second theory involves the scientific and spiritual dimensions of the buildings. The structures are built in line with astronomical movements of the sun, moon, planets, and stars, leading some to believe that it was in fact a kind of three-dimensional calendar, a much more elaborate version of Stonehenge in England. Settlers in the canyon would have gone there to worship at certain times of the year to be reminded of the order of the universe and their place in it. Ultimately, both these scenarios could exist. Certainly by anyone’s standards, a society that so fully integrated spiritual, scientific, and material aspects of life would qualify as a “great civilization.” If, however, by comparing North and South America you mean to ask why did North America not develop the exact same kind of societies that Central and South America did, then one answer to that may be population density. Central Mexico alone had 25.2 million people in 1491, making it the most densely populated place on earth. The whole continent of North America, by contrast, had 12–20 million people. As we see throughout human history and all over the world, higher numbers of people tend to lead to more highly stratified societies.

Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site. Last modified 2008. "Chaco Culture." National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities and the Department of Anthropology, University of Virginia. Chaco Research Archive. Last modified 2010. Seppa, Nathan. "Metropolitan Life on the Mississippi." Washington Post, 12 March 1997, Page H01. "Traditions of the Sun." NASA. Last modified 2008. "World Heritage Site." National Parks Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. Last modified 8 December 2009.

Stop Action and Assess Alternatives is a method for teaching students to think of historical events as contingent. They unfold from conscious decisions made by the involved parties who use the information available to them at the time of these events to make those decisions.

History is often presented as if things happened as they were supposed to happen. Yet with most historical events, there might have been any number of possible outcomes. At critical junctures, the people involved in the events made choices and acted in particular ways based on their values, their roles in the event, and myriad other factors. Using the Stop Action and Assess Alternatives technique helps students to discover that there is always more than one option when deciding what to do and more than two sides to every issue. Through a historical event—such as the Cherokee Removal example discussed below—students see that the involved parties were agents in what happened rather than passive observers.

After gaining background information about a particular historical event, which may come from the textbook or other sources, students analyze the historical event through primary source documents dating from the event’s critical junctures. The parties to the event are identified for students: in the example of the Cherokee Removal, these include Cherokee Indians, the State of Georgia, representatives of the U.S. government, and the media. The students are given documents one at a time that explain various incidents leading up to the event’s outcome. For example, students examine newspaper clippings, transcripts of parts of speeches, and an excerpt from the Supreme Court decision regarding the breach of a treaty between the Cherokee and the State of Georgia. After each document is read and discussed, students are asked to consider the options each constituent party had available to them at that moment. This Stop Action and Assess Alternatives pattern continues until all the documents have been read and discussed. The technique also can be used with such issues as the building of the Transcontinental Railroad, the Immigration Act of 1924, and the dropping of the atom bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As with the Cherokee Removal, multiple parties were involved in the decision making for these events and there were critical and distinct moments when decisions had to be made. These qualities lend themselves to the use of this technique. Stop Action and Assess Alternatives should not be used for events such as the outbreak of wars or economic transformations where timelines are too long and multivariate to be adequately addressed.

Ideally, students would receive three or more parties’ perspectives for each juncture along the way to the event’s culmination. However, this is not always possible. For example, with the Cherokee Removal lesson described below, there are multiple documents for some dates but only one document from one constituency group for others. It is important that students receive only the primary resources from the date under discussion. Students should not receive all sources at once.

- Members of the US government on all sides of the issue,

- Members of the Cherokee nation on all sides of the issue,

- The State of Georgia, and

- Members of the press.

- Be sure that students understand the nuances of the Cherokee Indians’ positions. For example, while there seems to have been unanimous opposition to the removal in the early years, some of the tribe’s leaders later changed their positions to favor removal but only as a means of ensuring the tribe’s safety.

To my first students, whose passionate desire to learn about Native Americans led me to learn more.

Ghere, David L. and Jan F. Spreeman. U.S. Indian Policy, 1815-1860: Removal to Reservations: A Unit of Study for Grades 8-12. Los Angeles: The Organization of American Historians and The Regents, University of California, 2000.

Perdue, Theda and Michael D. Green. The Cherokee Removal: A Brief History with Documents. Boston: Bedford Books, 1995.

Students analyze a variety of primary and secondary sources to determine the cause of the Jamestown starving time during the winter of 1609–1610.

This lesson provides a great opportunity for students to engage in real historical inquiry with prepared sources. The lesson is displayed in three locations on the site: the student view, which guides the student through the activity; the teacher view, which provides additional background information; and a PDF file that contains scripted instructions for the lesson.

Students first read a textbook passage about the Jamestown colony in 1609 and 1610. They then discuss how the writers of the textbook might have obtained their information, and go on to analyze primary source documents that expand upon the textbook account. Students essentially "do history" as they use a variety of sources to answer a clear, concise historical question—one that can be answered in multiple ways with the given data.

Another strength of this lesson is the document collection itself. A wide variety of primary sources offer greater insight into the reasons for the food shortage that resulted in the death of over 400 colonists in Jamestown during the winter of 16091610. Particularly helpful to teachers with struggling readers is the fact that the lesson includes not only the original documents, but also "modern" versions of the documents, written in language much more accessible to students.

While the detective log graphic organizer included in the lesson provides space for students to record source information, and the lesson itself provides a great exercise in sourcing, the documents themselves contain little source information. We recommend that teachers support students in using the available information about each document to understand its perspective and meaning. In general, the lesson provides good opportunities to engage in historical inquiry, to open up and go beyond the textbook, and to use primary sources to analyze the causes of an event.

Yes

Yes

A passage from Joy Hakim's Making Thirteen Colonies is included in both the student view and the teacher view of the lesson.

Yes

Yes

Yes

Teachers will want to support students in using information about the perspective of the various sources as they interpret each document's significance and meaning.

Yes

Yes

Documents are included both in their original form, and in an adapted "modern version" that will be more easily accessible to most students.

Yes

No assessment criteria are included, but the final writing assignment provides a great assessment of students' understanding and historical thinking.

Yes

Yes

These four collections of data and documents address Federal Indian policy in the late 19th century. The first set includes eight annual reports of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs from the 1870s, along with appendices and a map. The second set, Allotment Data, traces the Federal "reform" policy of dividing Indian lands into small tracts for individuals—a significant amount of which went to whites—from the 1870s to the 1910s. This set includes transcriptions of five acts of Congress, tables, and an essay analyzing the data.

The third set includes 111 documents on the little-known Rogue River War of 1855 in Oregon, the reservations set up for Indian survivors, and the allotment of one of these reservations, the Siletz, in 1894. The fourth set provides the California section of an ethnographic compilation from 1952.

This website contains 129 pamphlets, documents, and newsletters produced by or relevant to radical movements. Groups represented by one to 30 documents include the American Indian Movement; Asian Americans; the Black Panthers; the Hollywood Ten; the Ku Klux Klan, the IWW, and the Students for a Democratic Society. Additional situations covered include the Rosenberg case, Sacco and Vanzetti, and the Scottsboro Boys. Additional topics include birth control and the events at Wounded Knee. This is a small but useful resource on radicalism, political movements, and rhetoric.

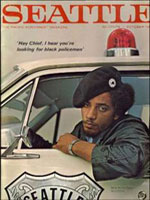

The long history of struggle for equal rights by various ethnic groups in Seattle, including Filipino, Chinese, Japanese, African, and Native Americans; Jews; and Latinos is documented on this website. Primary and secondary sources integrate labor rights movements with struggles for political rights, as is evident in the "special sections," that highlight the Chicano/a movement, the Black Panther Party, Filipino Cannery Unionism, the United Construction Workers Association, Communism, and the United Farm Workers. Each section brings together oral histories, documents, newspapers, and photographs that are accompanied by written and video commentary to provide historical context. The collection of more than 70 oral histories of activists is especially useful for understanding the lived experience of racism and its especially subtle workings in the Pacific Northwest. Together, these resources provide important national context for the civil rights struggle, too often understood as a solely southern phenomenon.