Pershing undoubtedly had complex views on race and American citizenship, probably not so different from his political ally and fellow Republican, Theodore Roosevelt. Given his command of African American “Buffalo Soldiers” in the 1898 Spanish-American War and his participation in the Wounded Knee Massacre of Lakota Indians just eight years earlier, it would seem that he held very contradictory views. To Pershing, blacks may have seemed like worthy soldiers, while Indians deserved genocide. On the other hand, as a military officer, Pershing was carrying out orders and we cannot assume these actions reflected his personal beliefs. Roosevelt, however, was in a different position. Unlike Pershing, who followed orders, Roosevelt gave orders and thus set the tone for race relations both in the military and in society at large. For example, Roosevelt was determined to see the cultural extinction of American Indians (while holding them up as “noble savages” nonetheless), but he also hosted black educator Booker T. Washington at the White House, a very controversial move, especially to white Southern Democratic politicians.

As a military officer, Pershing was carrying out orders and we cannot assume these actions reflected his personal beliefs

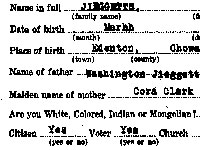

As the first two decades of the 20th century passed, the nation saw increased immigration from both Europe and Asia, as well as increased activism by African Americans, American Indians, and others who demanded equal opportunities and the end of discriminatory laws and customs. World War I was a watershed in these movements, as both African Americans and American Indians enlisted in the army. Blacks served in segregated units, but Indians did not. Indians had a highly ambivalent attitude about their senses of belonging to the American nation; after all, they belonged to tribal nations as well, nations which had long histories of government-to-government relations with the United States. Yet by 1918, the federal government had done a good deal to not only destroy Indian lives but to destroy that government-to-government relationship as well. Many Indians were resentful of these policies, but chose to join the military anyway. Why? Veterans have offered many reasons, one of which is that they believed that when America was threatened, their homelands were threatened. Many veterans saw themselves as warriors not only for their own tribal communities but for the U.S. as well. Despite their service alongside whites, there is no doubt that Indians experienced a high degree of discrimination in the military, as sensitively shown by Joseph Boyden in the novel Three Day Road. Both Indians and blacks sacrificed for the United States and felt that the country ought to treat them more fairly. Woodrow Wilson, a Democrat who had to maintain political support from southern white supremacist Democrats, vacillated on this issue (especially in his refusal to support anti-lynching legislation in Congress) and questions of African American integration in the military were essentially abandoned until after World War II. Wilson, like so many other policy makers, seemed to effectively ignore Indian concerns. Indians’ service with whites in the military might be explained by the emerging notion of “whiteness.” Whiteness is an analytical category that historians have used to explain the shifts in race relations created by immigration and industrialization in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. We must remember that men like Roosevelt and Pershing talked about “race” in what today we would think of as ethnic or national terms—there was an English race, an Irish race, a German race, an Italian race, and so on. Today, we tend to think of these ethnicities as “white,” though that idea was hardly solidified in the early twentieth century. Instead, a long historical process created “whiteness” and a white population out of many different nationalities once perceived as incompatible and even threatening to Anglo-Saxon Americans.

Racial hierarchies we believe to have always been in place were in considerable flux

Famously, Roosevelt believed in the “melting pot,” a phrase that we have come to associate with his belief in equality and the worth of all men, but which in actuality referred to his wish to see Americans with ancestry in Western Europe mix and marry one another. It was only those Americans who could jump into the melting pot—Asians, African Americans, American Indians, and others were explicitly excluded from Roosevelt’s vision of a strong American people. Yet, Indians were not segregated in military service, despite the fact that every American president had endorsed a policy that would essentially exterminate them. These policies had not wholly succeeded, but at the turn of the 20th century the American Indian population was at its lowest in human history. In this light, we can imagine that Indians were not perceived as a threat to whiteness in the same way that Southern Europeans, Eastern Europeans, Asians, and African Americans were. By the 1920s, immigrants from places seen as undesirable to Anglo-Saxon policy makers had increased so much that Congress passed the 1924 Immigration Act. This act installed quotas on immigrants from certain countries; in general, the number of immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe and Asia could not exceed 2% of those populations currently living in the US, as of the 1890 census. In other words, if, say, 100,000 people from China lived in the United States in 1890, then the US would admit no more than 2,000 people in a given year. Pershing, who was close to President Calvin Coolidge and had even considered a run for the Republican Presidential nomination in 1920, was present for the signing of this bill, indicating his support for it and what it represented for policy-makers’ hopes about the future racial composition of the United States. Of course, we now know that this policy ultimately did not achieve its intended effect, however much “whiteness” is taken for granted today. Indeed, what this period shows is that the racial hierarchies we believe to have always been in place were in considerable flux even as recently as 100 years ago. Pershing, Roosevelt, Wilson, and Coolidge were at the forefront of maintaining white supremacy, but they could not ignore the consistent—and insistent—protest of non-white Americans, nor should we ignore the fact that within white and non-white communities, there are very distinct groups with different histories who possessed varied responses to their situations in the United States.