"Facts are stubborn things." So said John Adams in his defense of the soldiers accused in the Boston massacre. Those words also serve as the title of the first episode of HBO's acclaimed film John Adams. Unfortunately, viewers familiar with Adams will find themselves immediately thrown off balance by dramatic renderings of "facts" that never happened. The film opens with Adams, awakened by an alarm, rushing through the streets of Boston. He finds bloody bodies strewn across a snow-covered square and a mob screaming that those responsible must be brought to justice. Offered a chance to enhance his reputation by defending the accused soldiers, Adams wrestles with the warning of his rabble-rousing cousin Samuel Adams that he must now choose sides in the emerging struggle. Adams defies his cousin and accepts the case. Unintimidated by a jeering gallery, he wins the soldiers' acquittal with an eloquent plea for justice: "Law is deaf as an adder to the cries of the populace." Success presents a new dilemma. Tempted by a royal official who dangles a lucrative place in the colonial legal system and enticed by the Sons of Liberty to run for office in Massachusetts, Adams renounces both options. "My family," he proclaims, "must take precedence." It is great theater. The virtuous and victorious citizen/farmer/lawyer returns home to his wife Abigail and their children.

Sadly, few of those details follow the record. Adams did not stumble upon the dead after the massacre or hear the crowd demand vengeance. He did not agonize about accepting the case, because he agreed immediately with the judicious Samuel Adams and other prominent dissidents that a spirited defense of the soldiers could only help those protesting British policy. Adams defended the soldiers by peppering high-minded reminders of the law's majesty with less elevated characterizations of the mob—including the part played by Indian/African American Crispus Attucks. Two of the soldiers were actually convicted of manslaughter in two separate trials. Finally, long before the massacre a British Satan had tried and failed to bribe Adams, who had already established himself—and been chosen for public office—as one of the most tenacious, effective, and visible of the colonists challenging Parliament's authority. Facts are indeed stubborn things.

Adams did not stumble upon the dead after the massacre or hear the crowd demand vengeance. He did not agonize about accepting the case....

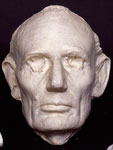

Why does it matter? John Adams was a smashing success. It attracted a wide audience and won 13 Emmy awards, surpassing the revered Eleanor and Franklin (1976) and Roots (1977) to become the most honored historical drama ever shown on television. The producer Tom Hanks assembled an extraordinarily talented crew. The people responsible for the architecture, costumes, makeup, accents, lighting, music, and special effects deserve all the accolades they have received. Specialists will appreciate their meticulous attention to detail. Colonial Williamsburg is carefully transformed into various 18th-century settings. Estates in today's Hungary become European mansions in the 1780s and 1790s. Exact replicas constructed in rural Virginia recreate the Adams family's modest homes, which still exist in Quincy, MA. An amazing sound stage becomes, through the magic of supplemental computer-generated images, the town centers and waterfronts of Boston, Philadelphia, and Washington, DC.

In place of the typically glittering aristocratic worlds portrayed in dreamy films such as Barry Lyndon (1975), in which ostensibly authentic settings convey a grandeur unattainable in the early modern world, John Adams convincingly mixes mud and manure, bad wigs and worse teeth, and harrowing glimpses of 18th-century life and death. Viewers are unlikely to forget vivid depictions of the smallpox inoculations performed on Abigail and her children, the amputation of a sailor's leg on board the ship carrying John to France, and the surgery Benjamin Rush performed on John and Abigail's adult daughter Nabby in the vain hope that she might survive breast cancer. Yet such scenes skirt melodrama. The English director Tom Hooper presents with admirable restraint incidents that might have been overblown, such as the horrific tarring and feathering of a customs official by a Boston mob, the surprisingly carnal reunion of John and Abigail when, after a separation of three years, she at last joins him on his diplomatic mission in France, and the visit John pays his alcoholic son Charles in a New York City hovel. Exquisitely framed, lovingly detailed interior scenes conjure up images from paintings by Caravaggio, Chardin, Rembrandt, or Vermeer. The soundtrack juxtaposes popular, religious, and classical music from the period with a rousing score that lingers in memory. Considered solely as a piece of filmmaking, John Adams is a ringing success.

John Adams convincingly mixes mud and manure, bad wigs and worse teeth, and harrowing glimpses of 18th-century life and death.

Superb characterizations abound. Laura Linney infuses Abigail Adams with sublime—albeit iron-willed—patience. The nuances expressed by Linney's raised eyebrows, even more than the gradations in her faint but persistent smiles, will be seared in viewers' memories. Scolding, satisfying, and succoring her husband and their children, Linney's Abigail conveys passion, longing, and occasional anger with a range and subtlety worthy of the formidable Mrs. Adams. Tom Wilkinson plays Benjamin Franklin as a mischievous, wise wit who too often speaks in aphorisms and only occasionally descends into caricature. Through glances and quick quips rather than windy speeches, Stephen Delane's Thomas Jefferson effectively signals his aspirations and ambitions for America and France, politically outmaneuvers Adams and David Morse's regal but stiff George Washington, and effortlessly charms everyone. As John Dickinson and Edward Rutledge, Željko Ivanek and Clancy O'Connor avoid coming across in the dramatic debates over independence simply as appeasers or fops. Rufus Sewell captures Alexander Hamilton's sly shrewdness and yearning for personal as well as national greatness.

Like many who have written about the film, I wish the writer Kirk Ellis (who also wrote Into the West [2005]) and the actor Paul Giamatti had given us a less bipolar John Adams. Giamatti careens from raging bull to wounded puppy, rarely showing the qualities of heart and head that enabled Adams to write some of America's most powerful and enduring letters and works of political philosophy. Giamatti's John is all haughty bluster or pathetic self-pity, his character unalloyed by Abigail's endearing mercy and doubt, Franklin's hard-edged insight, or Jefferson's lofty if fuzzy vision.

Yet the extremes of Giamatti's characterization do make some sense. His contemporaries knew that Adams was obsessive, priggish, and intolerant. The film reminds us that the querulous are sometimes provoked and the vain can have reason to be proud. A couple of scenes from the film must suffice to illustrate how effectively it conveys Adams's bottomless self-righteousness. When the principal authors of the Declaration of Independence were together negotiating in France in 1779, Jefferson observed that Adams "hates Franklin, he hates Jay, he hates the French, he hates the English. To whom will he adhere?" Jefferson noted that "his vanity is a lineament in his character which had entirely escaped me. His want of taste I had observed." Yet Adams was blessed with a "sound head" and "integrity," Jefferson concluded, and his "dislike of all parties, and all men, by balancing his prejudices, may give the same fair play to his reason as would a general benevolence of temper." Franklin assessed his undiplomatic colleague more succinctly: Adams, he wrote, was "sometimes, and in some things, absolutely out of his senses."

Franklin assessed his undiplomatic colleague more succinctly: Adams, he wrote, was "sometimes, and in some things, absolutely out of his senses."

Without quoting those ungainly letters, John Adams nevertheless deftly captures their authors' complicated interactions. Viewers see how Adams's clumsy directness in sophisticated European society exasperates the cagey Franklin and amuses the smooth Jefferson. We encounter Franklin, Jefferson, and Adams together again in Europe in 1784, and we hear them debating the future of the republic in a series of sharp observations encapsulating their rival orientations. When Adams proclaims that the proposed federal constitution will bring to the struggling nation only the order that the state constitutions—including the one Adams himself gave Massachusetts—had effectively provided, Jefferson snaps that the plan would "close off revolution to reaction." When Jefferson complains that Adams distrusts the judgment of the people, Adams snorts that Jefferson has "excess faith" in their wisdom. Finally, when Abigail and John bid Jefferson goodbye, Adams says evenly that he will miss the Virginian's company, to which Jefferson replies quickly, "and I will miss yours, Mrs. Adams." All three laugh, but the point is made: "exceptional" and "charming" as Abigail found the cosmopolitan Jefferson, she and her stolid husband preferred each other's company and knew they were better suited to their simple Quincy farm than to the courts of Versailles and London—or to the rigors of political life in the new nation's capital, whether Philadelphia or Washington.

Viewers hear John tell his adolescent son John Quincy, reluctant to depart on a mission to Russia, that "there are times when we must act against our inclinations." Together with Abigail's insistence, that sense of duty impels John to accept the vice presidency, "the most insignificant office ever devised by the mind of man." Even the signal successes of his long career—making the case for independence in Boston and Philadelphia, negotiating a loan from Holland during the War for Independence, and avoiding a disastrous war with France during his presidency at the cost to his prestige and his political prospects—earn Adams little acclaim. The poignant scenes in which the defeated president prepares to vacate the still-unfinished White House, then leaves via public omnibus as "just plain John Adams, ordinary citizen, same as yourselves" (except that he vibrates with resentment), are pitch-perfect.

The film's generous use of [John and Abigail Adams's] correspondence, which testifies to one of the great love affairs of American history, ranks among its greatest strengths.

Capturing in seven episodes the complex sensibility of John Adams and the still greater complexity of late 18th-century American politics is impossible. Ellis's screenplay and Hooper's direction give us the best rendition yet on film. To give Giamatti his due, perhaps the success of John Adams derives from the relentless awkwardness of his portrayal. Unlike Washington, Franklin, Jefferson, or Hamilton, the cerebral, brooding Adams remained uneasy in the public eye. He craved fame and feared history would deny him his share of glory, yet he never cultivated the qualities that would have won him affection and esteem. John Adams remains as difficult to like as his "dearest friend" Abigail is impossible to resist.

The film communicates Abigail's loathing for "the sin of slavery" and exposes the tragic compromises of the founders that insured its poisonous persistence. Oddly, it omits her equally precocious attention to women's rights, her pointed counsel that those framing republican government should "remember the ladies," and her husband's uncharacteristically evasive and entirely unconvincing rejoinder. John's gruff truculence in the face of Abigail's wisdom makes Giamatti's and Linney's portrayal of their profound bond even more extraordinary. The film's generous use of their correspondence, which testifies to one of the great love affairs of American history, ranks among its greatest strengths.

With so many virtues, then, why should historians worry about the film's factual errors? Ellis has made clear that his research extended beyond the best-selling book by David McCullough on which the film claims to be based. Of course, consulting recent scholarship on the social history of the Revolution might have sharpened the edge of Jefferson's jibes about Adams's views of "the people," just as closer attention to Adams's Thoughts on Government (1776) might have showed the decisive role Adams played in the spring of 1776 to counterbalance Tom Paine's endorsement of unicameralism in Common Sense (1776). Historiographical debates, however much we historians relish them, are hard to capture, and texts do not make good television. Of course there are limits to what any film can do. But Ellis read enough to know that Adams did not have to break a tie over the Jay Treaty, an "invention" he justified on the grounds that Adams cast more decisive votes in the Senate than any other vice president has ever done; that Rush brokered Adams's reconciliation with Jefferson before, not after, Abigail's death; that Adams did not ride out to see the Battle of Concord, and so on.

Historians can understand why writers and directors want to place their principal figures in the thick of things.

Historians can understand why writers and directors want to place their principal figures in the thick of things. But avoiding or at least acknowledging such examples of poetic license might help guard against the cynical (and, in this case, largely unwarranted) assumption that films never get history right, or the increasingly common and even more unsettling assumption among Americans that facts do not really matter anyway. Just as computer-generated images can enrich battle scenes and make cityscapes more "authentic," supplemental material on DVDs can deepen historical understanding. The extra material on the John Adams DVDs, by contrast, includes only a few subtitles with relatively insignificant details that add little to the experience of watching the film a second time. Such subtitles could have clarified the on-screen action, added further information about persons and events, and acknowledged when the filmmakers were inventing incidents or altering evidence for dramatic purposes.

Responsible teachers will want their students to know when John Adams departs from the historical record....

Responsible teachers will want their students to know when John Adams departs from the historical record, just as they will want to explore debates over the crowd's role in the American Revolution, explain the importance of Adams's decisive essays from the 1760s and his later writings on the U.S. Constitution, and examine the nature of female sociability and family dynamics. Rich as the film is, the DVD could have made it even better—at least for historians and their students. The same technology that lets filmmakers present convincing images of a half-built Washington, DC, enables them to enrich teachers' and students' appreciation of what historical dramas can and cannot do. Making the most of that technology could sharpen students' awareness of the unbridgeable gap between the vivid, unambiguous images on the screen and the documentary record with its inevitable omissions, its enchanting ambiguities, and its stubborn facts.