Friendly Fire

My cousin sent me this, is it accurate?

"The first German serviceman killed in WW II was killed by the Japanese (China, 1937), the first American serviceman killed was killed by the Russians (Finland 1940); the highest ranking American killed was Lt Gen Lesley McNair, killed by the US Army Air Corps. So much for allies."

This question is a little more complicated than it appears on the surface. For instance, Germany and Japan were not formally allied in 1937 (the Tripartite Pact allying Germany, Japan, and Italy went into effect in September 1940), and the 1937 action in China predated by two years Germany’s 1939 entry into World War II.

Likewise, historians usually consider the Winter War fought between Russia and Finland from 1939 to 1940 separate from the Second World War; in any case, it occurred well before the United States and Russia were allied, which did not occur until December 1941. (At the time of the Winter War, Russia and Germany had signed a non-aggression treaty and would remain in a state of uneasy neutrality until the German invasion of the Soviet Union in July 1941).

Lieutenant General Lesley McNair was indeed killed by United States Army Air Force bombs in July 1945 as part of Operation Cobra, the breakout from the Normandy beachheads following the June 6, 1944, D-Day invasion. Along with Lieutenant General Simon Bolivar Buckner (killed by Japanese fire on Okinawa in 1945), General McNair was the highest-ranking American officer killed during the war.

In a larger sense, the question speaks to the confusion and chaos that forms an inevitable part of battle, and to the mistakes that confusion creates. Fratricide (the accidental targeting of friendly soldiers) has bedeviled armies for centuries. The development of gunpowder and firearms, which increased the distance between forces on the battlefield and thus expanded the chances for miscommunication, misidentification, and mistargeting in combat, increased the incidences of battlefield fratricide.

The advent of long-range artillery and air power in the 20th century created still more opportunities. So-called “friendly fire” episodes reflect not soldiers’ incompetence, carelessness, or treachery but the impossibility of determining precisely what is going on and who is who in the lethal and confusing environment of battle. In the 19th century, the Prussian military theorist Carl von Clausewitz termed this confusion and ambiguity the “fog of war,” and it constitutes an unavoidable part of warfare.

Military history features many famous instances of fratricide. Confederate General Thomas J. Jackson was shot by friendly pickets as he reconnoitered after the battle of Chancellorsville in 1863. In May 1940, three German bombers attempting to strike a French airfield became lost and instead bombed the German city of Freiburg by accident.

Scores of American GIs during the Second World War wrote of being strafed by American or British aircraft, being the targets of their own artillery shells (often fired from miles behind the front), or accidentally receiving fire from adjacent friendly units. Increasing distance between combatants, the impossibility of perfect communications, and more frequent actions at night have all made distinguishing friend from foe more difficult.

Amidst the chaos and terror of combat, even the most capable and well-intentioned soldiers sometimes mistakenly target their own troops. Nor have technological innovations such as night-vision goggles and precision munitions eliminated the threat of fratricide in combat. The 2004 death of Army Ranger and former NFL player Pat Tillman during a firefight in Afghanistan from rounds fired by fellow American soldiers is perhaps the best-known recent example.

Geoffrey Regan, Blue on Blue: A History of Friendly Fire, New York: Avon Books, 1995.

Charles R. Shrader, Amicicide: The Problem of Friendly Fire in Modern War, Ft Leavenworth, KS: Combat Studies Institute, US Army Command and General Staff College, 1982.

Richard Townshend Bickers, Friendly Fire: Accidents in Battle from Ancient Greece to the Gulf War, London: Leo Cooper Books, 1994.

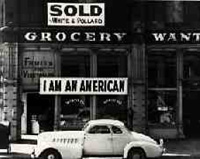

"Major General Omar N. Bradley and Lieutenant General Lesley J. McNair during the recent maneuvers of the the Third Army in Louisiana. General Bradley is seen pointing out one ot the maneuver situations to General McNair," 1942, Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress.