Hawaii—a U.S. territory since 1898—became the 50th state in August, 1959, following a referendum in Hawaii in which more than 93% of the voters approved the proposition that the territory should be admitted as a state.

There were many Hawaiian petitions for statehood during the first half of the 20th century.

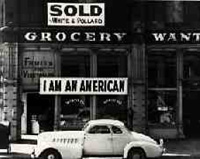

The voters wished to participate directly in electing their own governor and to have a full voice in national debates and elections that affected their lives. The voters also felt that statehood was warranted because they had demonstrated their loyalty—no matter what their ethnic background—to the U.S. to the fullest extent during World War II.

In retrospect, perhaps, the genuinely interesting question about Hawaii’s becoming a state is why it took so long—60 years from the time that it became a U.S. possession. There were many Hawaiian petitions for statehood during the first half of the 20th century. These were denied or ignored. Some in the U.S. had been convinced, even at the time of Hawaii’s annexation, that Hawaii had no natural connection to the rest of the states. It was not contiguous territory, most obviously, but 2,000 miles from the coast.

In retrospect, perhaps, the genuinely interesting question about Hawaii’s becoming a state is why it took so long.

Hawaii’s annexation in 1898 had much to do with the power of American plantation owners on the islands and the protection of their financial interests—both in gaining exemption from import taxes for the sugar they shipped to the U.S. and in protecting their holdings from possible confiscation or nationalization under a revived Hawaiian monarchy. There was considerable sentiment in the U.S. that annexation would be an unjust, imperialistic, and therefore un-American, move (Hawaii had more than sugar; it was a potential harbor and coaling station for naval vessels and was historically pressured in the 18th and 19th centuries for concessions by countries including Great Britain, Japan, and Russia).

Nevertheless, at the time of annexation the monarchy itself had only been in existence for a century, and originally consolidated power brutally, with the help of European sailors and firepower. Even by the end of the 19th century, a significant portion of the Caucasian residents of Hawaii had been born and raised there and considered themselves natives. Complicating the question was a large population of immigrant Japanese, Chinese, and Portuguese, all of whom had been originally encouraged to come in order to supply agricultural labor to the islands.

At the time of the vote, 90% of the population of Hawaii consisted of U.S. citizens.

Part of the decades-long reluctance to change Hawaii’s status from territory to state derived, both in Hawaii and on the mainland, from uncertainty and fear about granting electoral power to one ethnic group or another. This was not just Caucasian vs. ethnically Polynesian. Some ethnically Polynesian Hawaiians opposed the change from territory to state because, while they had come to feel comfortably “American,” they feared that the Japanese population on Hawaii (perhaps as high as 30%) would, under a universal franchise authorized by statehood, organize and vote itself into power to the disadvantage of the Hawaiians of Polynesian descent.

At the time of the vote, 90% of the population of Hawaii consisted of U.S. citizens. Hawaii’s importance in World War II had secured its identity as fully American in the minds of both Hawaiians and mainlanders. In addition, persistent and effective lobbying of Congressional representatives during this initial period of the modern Civil Rights Movement convinced enough members of Congress that this was the right moment to accept Hawaiian statehood, no matter what its racial makeup was.

Hawaiians themselves had been awaiting this for years, so much so that the “49th State” Record Label had been selling popular Hawaiian music since shortly after the War. As it turned out, Alaska entered as a state at the very beginning of 1959, making it the 49th, and when Hawaii came in several months later, it became the 50th state of the Union.