Pinpointing the causes of a vast, global event like the Second World War is a challenging task for the historian. Events—especially enormous, multifaceted events—have multiple causes and multiple inputs.

A proximate cause is an incident that appears to directly trigger an event...

To help analyze the effects of those different inputs, historians often classify an event’s causes into different categories. A proximate cause is an incident that appears to directly trigger an event, as the election of Abraham Lincoln in November 1860 and the shelling of Fort Sumter led to the outbreak of the Civil War. Such dramatic incidents are often the ones we think of as “causing” an event, since the connection between the trigger and the outcome appears both direct and obvious.

In their attempts to explore cause and effect, however, historians often probe more deeply beyond the “triggers” to locate trends, developments, and circumstances that contributed equally, if not more, to events. In the case of the Civil War, for example, historians often point to the growing sectional polarization that divided the nation in the 1840s and 1850s, the national debate over the future of slavery, and the divergent economic paths that distinguished North and South during the antebellum period. Those factors created the backdrop against which Lincoln’s election and the shelling of Fort Sumter led to full-blown armed conflict in the spring of 1861; those conditions contributed to a state of affairs in which a triggering event could exert such enormous influence and touch off a four-year war.

In the case of the Second World War, historians generally point to a series of conditions that helped contribute to its outbreak.

In the case of the Second World War, historians generally point to a series of conditions that helped contribute to its outbreak. The unbalanced Treaty of Versailles (which forced a crippling peace on Germany to end the First World War) and the global depression that enveloped the world during the 1930s (which led to particularly desperate conditions in many European nations as well as the United States) usually emerge as two of the most crucial. Those conditions formed the background against which Adolf Hitler could ascend to the position of German Chancellor in the 1930s.

Virtually all historians of the Second World War agree that Hitler’s rise to power was the proximate cause of the cataclysmic war that gripped the globe between 1939 and 1945. Without Hitler, a megalomaniacal leader bent on establishing a 1,000-year German empire through military conquest, it becomes extremely difficult to imagine the outbreak of such a lengthy and devastating war.

At the same time, Hitler’s rise to power did not occur in a vacuum. Much of his appeal to the German citizenry had to do with his promises to restore German honor, believed by many Germans to have been mortgaged via the Treaty of Versailles. The peace agreement forced Germany to accept full responsibility for the Great War, and levied a massive system of reparation payments to help restore areas in Belgium and France devastated during the fighting. The Treaty of Versailles also required Germany to disarm its military, restricting it to a skeleton force intended only to operate on the defensive. Many Germans viewed the lopsided terms of the treaty as unnecessarily punitive and profoundly shameful.

Hitler offered the German people an alternative explanation for their humiliating defeat in the Great War. German armies had not been defeated in the field, he held; rather, they had been betrayed by an assortment of corrupt politicians, Bolsheviks, and Jewish interests who sabotaged the war effort for their own gain. To a German people saddled with a weak and ineffective democratic government, a hyperinflated currency, and an enfeebled military, this “stab in the back” mythology proved an enormously seductive explanation that essentially absolved them of the blame for the war and their loss in it. Hitler’s account of the German defeat not only offered a clear set of villains but a distinct path back to national honor by pursuing its former military glory.

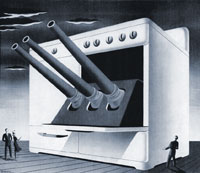

During the 1930s, Hitler’s Germany embarked on a program of rearmament, in direct violation of the terms of the Versailles Treaty. German industry produced military vehicles and weapons; German men joined “flying clubs” that served as a thin pretense for training military pilots. Rearmament and militarization provided appealing avenues for Germans seeking some means to reassert their national pride.

Politicians in Britain, France, and the United States...were reluctant to act to check Hitler’s expansionism without irrefutable evidence of his ultimate intentions.

Hitler’s racial theories provided more context, both for his explanation of defeat in the First World War and for his plans for a 1,000-year German empire. In Hitler’s account, Communists and Jews—whom Hitler depicted as stateless parasites who exploited European nations for their own gain—had conspired to stab Germany in the back in 1918. Creating the 1,000-year Reich required the creation of a racially pure cohort of blond-haired, blue-eyed “Aryans” and the simultaneous liquidation of ethnic undesirables. Hitler’s vision of a racially pure German nation expanding across Europe, combined with his aggressive rearmament programs, proved a powerful enticement for the German people in the 1930s. Politicians in Britain, France, and the United States, encumbered with their own economic troubles during the global depression, were reluctant to act to check Hitler’s expansionism without irrefutable evidence of his ultimate intentions.

Only later would the world learn that those intentions revolved around the methodical military conquest of Europe from the center outward, a process one historian of the Second World War has likened to eating an artichoke leaf by leaf from the inside out. That conquest began with the German invasion of Poland in 1939 and the attack on France and the Low Countries six months later. Hitler’s quest for more “living-space” for his empire led to the invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941. By March of 1942, Hitler’s fanatical desire to conquer Europe—along with Japan’s concurrent push across East Asia and the Pacific—had plunged the world into a war that would last nearly six years and cost the lives of more than 50 million soldiers and civilians: by far the largest catastrophe in human history.