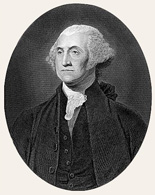

Monticello: Jefferson's Experiment

Curator Elizabeth V. Chew introduces TAH teachers to Monticello as Thomas Jefferson's 'laboratory,' a testing ground for ideas he imported from around the world. Chew also looks at the lives of enslaved people at Monticello and how their experiences were both similar to and different from those of others enslaved throughout the Mid-Atlantic.

Elizabeth V. Chew: This visitor center facility opened in 2009 and it has radically improved our ability both orient our visitors to just explain to them why Jefferson is important and so, why they're here, and to engage and educate.

This exhibition is really one of four that's in the building. This is the largest one, it's the one that is intended to put the house, which is the one piece of Monticello that mostly everybody sees, in the context of Monticello writ large, Monticello as a 5,000-acre working plantation.

If you look up at this light pencil drawing on the banner here, you can see the view that the young Jefferson would have seen from Shadwell, looking over across the Rivanna River, the little low mountain in the front here is Monticello. The high mountain behind Monticello is the mountain that Jefferson called Mountalto, and he bought—he bought what he could see from his mountain of that mountain in the 1770s. And so, as a boy, the little mountain just drew him and he had a dream of living there as an adult when he was a teenager. And that would have been the least practical place you could ever live. In a time when the river was a major means of transportation, where getting around was difficult at any time, where water was a constant problem and need, to live on a mountain made no sense. He really elevated ideals over being practical, over practicality.

The central section in the middle of the room here goes through and gives examples of Jefferson's just complete and total dedication to doing what he would call gathering, recording, and sharing and disseminating this idea of useful knowledge, whether it was related to science, to farming, to government, to transportation, to what you could and couldn't grow somewhere. He was interested in really every point of knowledge on the human spectrum. And nothing—there was almost nothing that was too small for his attention.

We have several really fun kind of interactive elements in the exhibition, and this one uses Jefferson's travels, both in North America and in Europe, and it shows people what, when Jefferson was traveling, what he was doing, and he said it himself, that he was gathering ideas that would be useful—'useful'—back in this country. So what we do is follow his travels—and I'm looking at southern France right here—and we talk about everywhere he went, what he was looking at.

So here we are: viticulture or wine-growing in the Burgundy region of France, or ancient architecture in Orange, France. He was also completely obsessed with the idea of people in this country growing olives. He thought that olive oil was going to be the new revolution and that the rice planters in Southern Carolina should stop growing rice and grow olive trees. And he really worked hard to convince them of that. Really, he's so interested in these little details of things that he thinks are going to help him come back here, share the ideas, and even put them to use himself.

So, this is a fun way, and, all as you all know way better than I do, young people love this kind of thing.

Elizabeth V. Chew: So I've talked about how the center is about his dedication to all this gathering and sharing and disseminating. This short wall here is dedicated to a horizontal look across the social spectrum at Monticello. Because we obviously know that Jefferson and his elite family in their 'big house,' they're the tip of the pyramid here, but obviously everything that happens that makes his household run, that makes his cash crops grow, is done by the labor of enslaved people.

So we also look across the spectrum of the enslaved community at people working in the fields versus enslaved people who work in the house or in the [?] industries, and we compare those also to hired white people. There were some hired white workers here who did things like, well, build a house, for one thing, or serve as blacksmiths or certain kinds of carpenters. They also trained enslaved people to do these kinds of jobs.

We've learned an amazing amount about the lives of enslaved people all over the plantation. So, what we know is that enslaved people owned material goods. We tend to have a notion of slavery, I think, or at least I used to, as being very fixed and abstract and this big box of awfulness and yes, it is that. But you can also come to understand it in a much more textured way where you see—we know a great deal about the names and activities and lives of the individual people who lived here in slavery and what happened to their descendants. And that combination of Jefferson's record keeping, archaeology, other kinds of written records, and then genealogy and oral history that we've been doing here for 40 years.

So we know that people who worked in the fields owned the same kinds of really fashionable tablewares that slaves who worked in the house and lived up on the mountain owned and that, in many cases, are the same kinds of things being used in the big house. Slaves had several different ways of making money. Jefferson preferred to give cash incentives to slaves rather than use harsh physical punishment, so some skilled slaves received cash money. Slaves also kept poultry yards and gardens on their own time and sold the products of those, both to the big house and sometimes in markets in towns. Slaves were paid by Jefferson for doing particularly onerous jobs like cleaning out the sewers underneath the privies, and slaves were given tips by visitors quite routinely. So with the money that people here in slavery owned, we know that they went into town on Sundays and shopped in stores. Scholars have studied shopkeepers' ledger books and found that there are records of slaves coming in and buying things.

So what we see here, I think, is examples of how enslaved people survived in a system that denied them their basic humanity. We see how people figured out ways to just get through it. And we see families over generations here whose descendants go on actually to be very involved in all kinds of work towards emancipation and later civil rights.

Elizabeth V. Chew: On the wall here behind you, we break down Monticello into four areas. We look at gardens, agriculture, plantation industries, and the house. And my interest here was making it all on the same plane. Often we tend to privilege the house over everything else. I think Jefferson saw it as being all of a piece.

So we look at how he puts what he considers to be this useful knowledge to work, in all aspects of his operations here, whether it's what he grew in the garden, his attempts to grow grapes to make wine, his intense interest in the technology of agriculture. For example, he himself invented a kind of plow moldboard. People think of him as being an inventor. He was mostly a creative adapter because of all these things he learned about, wrote down, and then later used here at Monticello. The one thing that he ever truly invented was a plow moldboard. And we have a recreation plow right here that shows this curved—it's the curvy wood part that sort of turns over the soil once it's cut by the metal blade. So he had witnessed people plowing in France that he thought were really inefficient, and he has this geometric idea for the shape of a moldboard that will do a better job with less resistance in turning over the ground. So he has this plow made here at Monticello and he writes to all of his people all over the world to tell them about it. Even though he won several awards for it, it was never really widely adopted.

The Garden Book is really a bravura demonstration of his record keeping interests. Let's see. We have a little facsimile of it right here, and it's really hard to see, but he basically—he started it as a young man still living at Shadwell. After his retirement here in 1809, he really does it every single year in earnest, where he writes down, keeps a chart where he writes down everything he plants and when, when it sprouts, how it does, and then eventually 'when it comes to table,' which means when they get to eat it in the house, and when it goes to seed. And he does this every year for over 20 years. He doesn't care if something doesn't do well, he just tries something else. His interest is really in what will grow well in this particular climate here in Albemarle County, Virginia. He wants to know what he can grow here that will be useful. So things like benne or sesame, he grows that. These hot peppers a friend in Texas sends him. There are a number of examples of things that people send him that he tries to grow. He really really really wants to grow wine grapes, but he never can. He would actually love the fact that wine is such a big deal now in Virginia.

So even though he has this amazingly gorgeous, 1,000-foot-long garden, we know for a fact that this garden was not primarily meant to furnish the table. We know that because from the beginning to the end of Jefferson's life at Monticello, we have record books kept by the women of his family, the white women of his family, recording purchases of large quantities of garden produce from slaves, and this is one of them right here. So Jefferson's garden was mostly a laboratory and an experiment. If something came to the table, that was great, but they were not relying on it. They had this very good backup plan that they had to use almost every week.

Jacqueline Langholtz: Tell me more about yourselves and what, when you woke up this morning or heard about this trip two weeks ago, you wanted to take away from it.

Teacher 1: Well, I teach fifth grade, so it's mostly U.S. geography, that's the emphasis for our course, so—

Teacher 2: Westward expansion?

Teacher 1: Yes, that's really—

Jacqueline Langholtz: Okay, so Lewis and Clark's why you're here? Great, okay.

Teacher 1: Especially the scientific discoveries and we're putting more of a science emphasis on the flora and fauna of different areas, too. So what their findings were and also what they found—yeah, I think it'll be very helpful.

Jacqueline Langholtz: Wonderful. Great.

Teacher 2: Is there information on the relationship with Jefferson or his time period with the Native Americans, because that's one of the things that we try to do as we move from region to region is that Native American element of that region.

Jacqueline Langholtz: Yeah. Yeah. So the question was the relationship that Jefferson specifically had with Virginia Indians?

Teacher 2: And his contemporaries.

Jacqueline Langholtz: And his contemporaries. Okay. Jefferson's own and only self-published book, his own book, Notes on the State of Virginia, would probably be a good resource and that's a primary resource there. That's a field that I think people are really just beginning to explore and learn more about, and I think you'll hear some different opinions about, what did that really honestly look like, and I think you'll see a lot more scholarship about that coming out, I hope so.

Teacher: Do you think that it was typical what Jefferson had here, was that a typical economy for a plantation in the South?

Elizabeth V. Chew: No. You mean the slaves—

Teacher: What you found in the—

Elizabeth V. Chew: Oh, yes, I do. Yes, I do, actually. I think Jefferson was unusual in what he said he wanted here was to use things like work incentives and not harsh punishment, that keeping families together made people more productive because they were happier. That was not typical.

Teacher: Right.

Elizabeth V. Chew: Yeah. But I think that the slaves raising gardens and chickens, perfect, totally normal. Slaves owning goods across the South, completely typical.

Teacher: Wow.

Elizabeth V. Chew: It's probably the thing that most people don't know about slavery, that is most surprising to them. That is absolutely the case. In the very very deep South, like Louisiana, and maybe even Alabama, it's less so, but in the Mid-Atlantic, the Carolinas, it's completely the way it is.

Teacher: And these are very high-quality goods that they had, then, would that have been typical as well, that they had—

Elizabeth V. Chew: It's what was available. You know, they're on the spectrum of things you could have. They're not at the very top. Jefferson has some Sevres porcelain from Paris, but he has this stuff also.

Teacher: Wow.

Elizabeth V. Chew: So it's sort of like your everyday china, as opposed to your grandmother's fancy china, but it's absolutely the same thing that any of the other

Teacher: And where would that have come from, from Europe as well?

Elizabeth V. Chew: Stores in the area. These would have still been English by this time, but they would have been available, widely available in stores in every town in the U.S.

Teacher: So, typical. Like Pfaltzgraff kind of.

Elizabeth V. Chew: Yeah, he could have gone to Charlottesville on Sundays and bought them. Merchants stayed open on Sundays so the slaves could come, actually. And they bought things like tablewares and then clothing, things like buckles and buttons and hooks for clothing that they would make themselves and fabric. Jefferson gave slaves basic food, two sets of clothing a year, blankets, and then cook pots when they got married, but people had a lot more than that, that they acquired through their own incredible ingenuity and entrepreneurship basically.

Teacher: That's interesting.

Elizabeth V. Chew: It took a lot, it took so much effort and ability to survive laboring like that.

Teacher: Is there any evidence that slaves worked with Jefferson intensely on his inventions and machinery?

Elizabeth V. Chew: Oh, yeah. That's such a good question.

Jacqueline Langholtz: What was the question?

Elizabeth V. Chew: Whether slaves worked with him. Slaves definitely made the plow. I think, he lived in this cerebral region of his brain that he never, hardly ever went out of. I think he just saw—he drew all these geometric models of how he derived it. I think he kind of felt it in the abstract and then he had slaves—made it, build it, and then try to use it. But they probably were not involved in the design decisions.

Teacher: Right. Because that would have taken a lot of skill to craft.

Elizabeth V. Chew: No kidding.

Jacqueline Langholtz: Well, I get these same feelings about what you see in the house, or even the Campeachy chairs, even the friezes. So Jefferson is—he's the one traveling, he's the one reading, and then he's saying oh, I want this in my house. And then you have John Hemmings and James Dinsmore. But John Hemmings, who has not traveled, who hasn't read about these—

Elizabeth V. Chew: Who wasn't educated.

Jacqueline Langholtz: Right, who wasn't educated, making 3D versions, bringing Jefferson's physical ideas to life. It's just incredible to me.

Teacher: Wow.