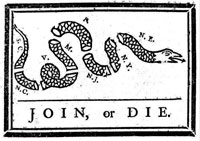

The "Join, or Die" snake, a cartoon image printed in numerous newspapers as the conflict between England and France over the Ohio Valley was expanding into war—"the first global war fought on every continent," as Thomas Bender recently has written—first appeared in the May 9, 1754 edition of Benjamin Franklin’s Pennsylvania Gazette. The image displayed a snake cut up into eight pieces. The snake’s detached head was labeled "N.E." for “New England,” while the trailing seven sections were tagged with letters representing the colonies of New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. The exhortation "JOIN, or DIE" appeared underneath the image.

Lester C. Olson points out that Franklin might have seen images of snakes divided into two segments that had been published in Paris in 1685, 1696, and 1724 with the similar caption "Se rejoinder ou mourir." The image in the Pennsylvania Gazette followed an article reporting the recent surrender of a British frontier fort to the French army and purported plans of the French, with their Indian allies, to establish a massive frontier presence with which to terrify British settlers and traders. The article ended with the surmise that the French were confident they would be able to "take an easy Possession of such Parts of the British Territory as they find most convenient for them" due to the "present disunited State of the British Colonies" and warned that the French success "must end in the Destruction of the British interest; Trade and Plantations in America."

Franklin was opposed in his efforts to unify the colonies by representatives of some of the colonial assemblies

A longtime advocate of intercolonial union in dealings with Indians, Franklin helped make such a union an important agenda item for the Albany Congress, convened shortly after the snake image was published, on earlier orders from the Board of Trade, the British advisory council on colonial policy, with the goal of establishing one treaty between all the colonies and the Six Nations of Iroquois. As a commissioner to the congress appointed by the governor of Pennsylvania, Franklin was opposed in his efforts to unify the colonies by representatives of some of the colonial assemblies intent on maintaining control over their own affairs.

Robert C. Newbold has speculated that Georgia was probably excluded from the snake image, "because, as a defenseless frontier area, it could contribute nothing to common security." Only three laws had been passed in Georgia since its founding as a colony in 1732, prompting a historian of the colony and state to conclude, "The hope that Georgia might become a self-reliant province of soldier-farmers had not succeeded, and even the early debtor-haven dream had not come to pass." Delaware, Newbold added, "shared the same governor, albeit a different legislature, as Pennsylvania; hence the Gazette probably considered it as included with Pennsylvania."

As with the snake image, the Albany Plan, drafted during the congress, did not include Georgia and Delaware in its proposed colonial union for mutual defense and security, specifying only Massachusetts Bay, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina. The segmented snake image was revived in a number of newspapers during the 1765 Stamp Act conflict, again without reference to Georgia and Delaware. In 1774, when the segmented snake image, along with the "Join or Die" slogan, was employed as a masthead for newspapers in York, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania, a pointed tail labeled "G" for Georgia had been added.