Did Benjamin Franklin Bring Pornography to America?

Is it true that Ben Franklin brought pornography to America?

Benjamin Franklin was "the primary publisher . . . in America from the start of his business in 1729 until he retired early in 1748" at age 42, according to J. A. Leo Lemay, the author of a projected seven-volume biography of the founding father. During this period, Franklin was a prominent bookseller as well publisher and printer, and as such, sold many books imported from Europe.

Lemay has reprinted a selection of titles that Franklin desired to sell, listed in published advertisements from 1739 and 1740, a few of which might seem from their titles to include salacious content, e.g. "Arraignment of lewd women" and "Garden of Love." Lemay, however, refrains from categorizing these works or any others sold by Franklin as pornographic. Likewise, no respected biographer of Franklin has asserted that he imported pornography for sale.

Numerous authors nevertheless have repeated the claim that Franklin was one of the first or in some accounts the first American to own a copy of John Cleland's Fanny Hill; or the Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, an English novel containing explicit descriptions of sexual encounters and historically considered to be one of the most widely read erotic texts.

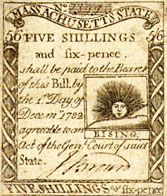

The first installment of that book, however, was not published until November 1748, some 10 months after Franklin had retired as a bookseller, and although Lemay notes that Franklin did continue until 1757 "to guide the choice of pamphlets and books issued" by the publishing firm that he had founded, importation of Fanny Hill into America did not occur until much later in the 18th century, according to Joseph W. Slade, author of a reference work on the history of pornography.

Just when the sale of pornographic novels began to thrive in Europe is a matter of contention among historians. Many scholars, including Donald Thomas and Steven Marcus, identify the latter part of the 18th century as the period of its flourishing, while Peter Wagner contends "the pornographic novel and related fiction were in full bloom" prior to the publication of Fanny Hill.

Cathy N. Davidson reports "some evidence to suggest" that Isaiah Thomas, a claimant to the title of publisher of the "first American novel," in addition was the first American publisher to import Fanny Hill, but she also notes that an English bookseller wrote to Thomas that he did not send that book "to my Customers if I can possibly avoid it." Davidson concludes that Thomas, had he imported the novel, "would have gone to considerable lengths to hide that fact." We might conclude that Franklin, had he imported pornography, would have done the same.

A few of Franklin's own writings have been categorized as potentially obscene, though none was published under his own name during his lifetime. A federal circuit court judge in a concurring opinion to the 1957 obscenity case United States v. Roth (which became the basis for the landmark Supreme Court case Roth v. United States) cited Franklin's "Advice to a Young Man on the Choice of a Mistress" and "The Speech of Miss Polly Baker," as two works "which a jury could reasonably find 'obscene,' according to the judge's instructions in the case at bar." The judge concluded, "On that basis, if tomorrow a man were to send those works of Franklin through the mails, he would be subject to prosecution and (if the jury found him guilty) to punishment under the federal obscenity statute."

J. A. Leo Lemay, The Life of Benjamin Franklin, vol. 4, Printer and Publisher, 1730-1747 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 378, 392, 401.

Stacy Schiff, A Great Improvisation: Franklin, France, and the Birth of America (New York: Henry Holt, 2005), 236; Joseph W. Slade, Pornography and Sexual Representation: A Reference Guide (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001), 3: 834.

Peter Wagner, Eros Revived: Erotica of the Enlightenment in England and America (London: Secker & Warburg, 1988), 231-32.

Cathy N. Davidson, Revolution and the Word: The Rise of the Novel in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986), 84, 88-89; United States v. Roth, 237 F. 2d 796 (2d Cir. 1957).

Max Hall, Benjamin Franklin & Polly Baker: The History of a Literary Deception (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1960).

Image of Franklin reading: Detail of 1766 painting by David Martin, now at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, Philadelphia.