What Is It?

A discussion that moves students beyond either/or debates to a more nuanced historical synthesis.

Rationale

By the time students reach adolescence, many believe that every issue comes neatly packaged in a pro/con format, and that the goal of classroom discussion, rather than to understand your opponent, is to defeat him. The SAC method provides an alternative to the "debate mindset" by shifting the goal from winning classroom discussions to understanding alternative positions and formulating historical syntheses. The SAC's structure demands students listen to each other in new ways and guides them into a world of complex and controversial ideas.

Description

The SAC was developed by cooperative learning researchers David and Roger Johnson of the University of Minnesota as a way to provide structure and focus to classroom discussions. Working in pairs and then coming together in four-person teams, students explore a question by reading about and then presenting contrasting positions. Afterwards, they engage in discussion to reach consensus.

Teacher Preparation

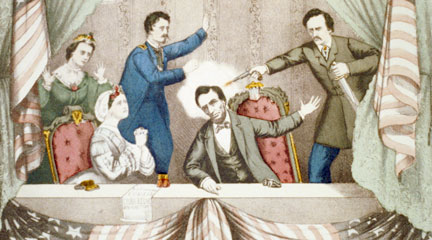

1. Choose a historical question that lends itself to contrasting viewpoints. For example, we illustrate the SAC below with the question "Was Abraham Lincoln a racist?" but many other questions lend themselves to the technique. For example, "Was dropping the atomic bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki necessary to defeat the Japanese?" or "Could the Constitution have been ratified if slavery had been abolished?" and so on. 2. Find and select two or three documents (primary or secondary sources) that embody each side. (Remember that you can pull these from existing document collections on the web or in print.) 3. Consider timing, make copies of handouts, and plan grouping strategies. The time you will need for a SAC that uses about four documents will depend on the amount of experience your students have with the activity structure and the difficulty and familiarity of the documents. Plan on using about two class periods for your initial SAC.

In the Classroom

Modified and adapted countless times by researchers and teachers, the technique has five basic steps (See Handout 1) with procedures to display for students. 1. Organize students into four-person teams comprised of two dyads. 2. Each dyad reviews materials that represent different positions on a charged issue (e.g., "Was Abraham Lincoln a racist?"). See Handout 2 that helps students track their analysis and prepare their positions. 3. Dyads then come together as a four-person team and present their views to one other, one dyad acting as the presenters, the others as the listeners. 4. Rather than refuting the other position, the listening dyad repeats back to the presenters what they understood. Listeners do not become presenters until the original presenters are fully satisfied that they have been heard and understood. 5. After the sides switch, the dyads abandon their original assignments and work toward reaching consensus. If consensus proves unattainable, the team clarifies where their differences lie.

Common Pitfalls

Students' debate framework starts early and runs deep. Even when told that they need to understand—not undermine—an opposing position, students will try to find holes in their opponent's positions and aim to refute them. We recommend

- Introducing the idea of "active listening" to your students and having them practice it in dyads for a few minutes

- Establishing the rule: Jot down notes when confused, do not interrupt the presenters

- Making sure students can refer to the procedures throughout the activity by posting them or making handouts

As students start to see other perspectives and nuance in the materials, the absence of a certain answer may confuse them. We recommend reassuring students that uncertainty and complexity are expected during this activity. Encourage them to make notes that specify their confusion, new ideas or questions.

Example

Was Abraham Lincoln a racist? Background for the teacher: How we judge people in the past is at the core of historical understanding. Should we think less of Thomas Jefferson because he was a slave owner? How should we regard forms of slavery sanctioned by the Bible? How do we regard people who believed in witches? Or that the ordeal was a way to establish truth? In other words, how do we judge people in the past, people who thought differently from us and perceived the world using different beliefs and assumptions? This question pivots on two opposing stances: first, that there are a set of universal virtues—kindness, fairness, openmindedness, goodness, decency, and tolerance—that transcend time and space. Alternately, the opposing stance sees human virtues as relative, shaped by the dictates of particular settings and circumstances. In this sense, an "enlightened person" looks very different on questions of human decency depending on whether he or she lived in the 13th century, the 19th, or today. Ideas related to the question of how we judge the past will come up in students' conversations. This is how it should be and as directed in the Common Pitfall, students should be encouraged to track these ideas as pairs prepare and present and then to discuss them as they try to reach consensus. In this Structured Academic Controversy, this question of how to judge the past is considered by examining the person and the time of Abraham Lincoln. Specifically we ask, Was Abraham Lincoln a racist?

Racist, n., one who believes that his or her race confers an inherent superiority over others. (Webster's Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary)

The two handouts will help you introduce and set up this activity and there are four documents that accompany this SAC. Each dyad should get all four. Acknowledgments. We thank Professor Walter Parker at the University of Washington's College of Education for helping us see the enduring value of the SAC approach in the history classroom.