The Election of 1932: Photographs of FDR

- Library of Congress

- National Archives and Records Administration

- Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum

What can a photograph of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1932 reveal? Donald A. Ritchie looks at the people captured in this photograph, including FDR, his son James, Eleanor Roosevelt, and later Secretary of the Senate Mark Trice, and considers the significance of how Roosevelt stands and presents himself.

In my book I use this picture of Franklin Roosevelt arriving at the capital in 1932. Now we have a picture before that of Roosevelt riding with Herbert Hoover from the White House to the capital. These are two men who had been friends since 1917, they had worked together in the Woodrow Wilson administration, they had considered running as a Hoover/Roosevelt ticket for the Democrats in 1920, except that Hoover decided that he was really a Republican and went for them and Roosevelt went for vice president that year on the Democratic ticket. Then they sort of drifted apart, and in 1928 Roosevelt became governor of New York, Hoover became president and then they became rivals in 1932. Their relationship became more and more bitter to the point when they rode from the White House to the capital they practically didn't speak to each other.

At this point they've arrived at the Capital, Hoover is nowhere to be seen, but Roosevelt is out standing with his family. Roosevelt had been stricken with polio in 1921 and he had lost the use of his legs. This was going to be an issue in the election of 1932—would we elect a president who was paralyzed? Hoover knew about Roosevelt's condition and he speculated that the nation would not elect a "half-man" and that Roosevelt might collapse in office. I think Hoover thought that Roosevelt would not be an effective campaigner that he would probably be too weak to carry on a campaign. Roosevelt, in fact, is an enormously vigorous campaigner, [he] spends the time traveling back and forth across the country, being photographed constantly. Hoover, who has been working seven days a week late into the night over the problems of the Depression, has aged terribly in his four years—the photographs of him make him look 82 years old. So Roosevelt looks much healthier and more vigorous than Hoover does.

Roosevelt goes to great lengths to disguise his illness. People wrote stories about it, saying that he had been stricken [with polio] and people knew he had polio, that had been front-page stories in 1921. But, he did not appear in public in a wheelchair, he had leg braces, he had his pants tailored to cover the braces, he walked with a cane, and he always walked with a strong-armed person next to him. During much of the campaign his son James—who is standing here in the bowler hat—was the one who stood next to him. Especially in the back of the trains, when they would step out, the Roosevelt family would be all around him.

Roosevelt had a nice little way of introducing his family to audiences so that you were all part of the family essentially. He would always end with "and my little boy Jimmy," because Jimmy was two or three inches taller than he was and everybody would laugh at that point, but that would diffuse the issue that he was hanging on to Jimmy's arm really to keep himself standing.

So here is Roosevelt dressed for the inauguration, in his top hat, striped pants, the cane, holding on to Jimmy's arm. Standing next to them is Eleanor Roosevelt, who does not look like she's really happy to be there. Eleanor Roosevelt was a very independent-minded person; she and her husband had really developed independent lives, especially in the 1820s. She was very politically active and she really did not look forward to him being President of the United States. She did not campaign very much with him, she hated being on smoke-filled trains—which went very slowly, because of Roosevelt's condition he didn't like the train to speed because he was in a wheelchair in the train. So it went relatively slowly across the country. Then you would stop in these little towns; everybody got out the back [to] say pretty much the same things to the same types of crowds. The wife was supposed to stand pleasantly on the side, receive a bouquet of flowers, not say anything. Eleanor was just beside herself. She actually left the campaign trail in mid-October to go back to New York to teach in the school—the private school—where she was teaching American history at the time.

She—I'm not even sure she voted for Franklin Roosevelt in 1932, she may have voted for Norman Thomas. She really did not want him to be President of the United States and you can just see this in her body language and the way she's looking at this point. She had great anxiety over what this was going to do to [him]. The irony is that she became a great first lady. She realized this gave her an opportunity to promote all the issues she was interested in, to travel and to do things. But she didn't know that on March 4, 1933, this was all coming in the future.

Now the reason I have this photograph is because of the young man standing on the edge of the picture, looking very nervous, in striped pants and a cut-away: his name is Mark Trice. Mark Trice came to the U.S. capital during World War I as a pageboy and then he stayed; that was not uncommon in those days, people were just drawn to politics. He stayed and he worked for the Sergeant at Arms and he was the Deputy Sergeant at Arms in 1933. He was a Republican appointee.

In February of 1933 the U.S. Senate fired the Sergeant at Arms. He knew that he was losing his job because his party had lost the majority. He was an old newspaper reporter and he wrote a story about what he really thought about Congress to be published in the March edition of a magazine, not realizing that the March edition came out in February. When it came out—and when his critical comments about Congress were in there—the Senate called him forward to demand to know what he had in mind, and then fired him. That made Mark Trice the acting Sergeant at Arms for Franklin Roosevelt's inauguration. He was very young, he was very scared, he was also very Republican, which is interesting that he was in charge of this Democratic president's inauguration.

When I came to work for the Senate in 1976, Mark Trice was still around—he had been a variety of functions, he had been the Republican secretary, he'd been the Secretary of the Senate. He was retired at this point but he couldn't keep away from the capital. He'd come to the Senate Historical Office and tell us stories—just sit there and tell wonderful stories. He gave us this photograph and other photographs of the time. We tried desperate to do an oral history interview with him; I really wanted to record what he had to say. But he felt that he had kept the confidences of these politicians for so long that he could not record it. And he literally one day ran out of the office when we tried to tape-record his stories that he was telling us. But this photograph from him, I think, is a great keepsake of that moment [and] it tells you a lot about those people and about the way that they're presenting themselves to the world.

Photographs are part of the documentary evidence, they're not exclusive, you can't—unless you've done the research to find out what's really going on here—you can look at this picture and not really realize how Roosevelt is presenting himself. But if you look closely you can notice that there's just something that's a little odd about the cuffs of his pants, the way they've been cut, and they're there to cover these very heavy steel braces that Roosevelt used. There's actually a small piece of the brace that goes underneath the heel that you can see there. When he's sitting down sometimes you can see a little bit more of it.

Franklin Roosevelt only mentioned his braces once in public. That was in January or February of 1945 when he had just come back from Yalta. He went to speak in the House chamber and instead of standing, he sat at a table—it was the only time he ever sat for a major speech like that. He apologized to the Congress, but he said, "With 10 pounds of heavy steal around my legs, it's easier for me to sit down." That was the sole reference he ever made to those braces. You can actually see the braces in other pictures where he's sitting down. But there's just a slight awkwardness to the pose.

He walked by pushing his legs forward. Actually, when he became ill, he developed his upper body so he had very powerful arms and shoulders. And getting on and off of trains they actually built parallel bars and he swung his way down. So he gave the illusion of walking, but he was never able to walk again after he was stricken with polio in 1921.

There's a misconception that Roosevelt hid his polio. The fact of the matter is every year on his birthday children used to send dimes to the March of Dimes in his honor. They would have pieces on newsreels in the movie theaters; they would actually raise money at movie theaters. Roosevelt became a poster person for polio victims, and eventually of course, when he dies, they put his face on the dime because of the March of Dimes. His illness actually contributes to the final solution to coming up with a cure for polio or prevention for polio. But what he was really trying to show was that he was not limited by polio. That he could go around, he could get anywhere, he could do anything, even though he couldn't walk well.

Some of the people thought he was just lame. Of course the editorial cartoonists used to draw pictures of Roosevelt running, jumping, jumping out of an airplane in a parachute, chasing a bull with a pitchfork, doing the types of things that editorial cartoonists like to do. Which people had the sense that Roosevelt could move. People could see Roosevelt standing up in the newsreels and all the rest. Now if you were in a crowd who had come to see Roosevelt, you would see that he was in some cases physically lifted out of a car, you could see that he was not able to walk smoothly, but he was able to get from point A to point B. They would often put potted plants and other things in front of him so you didn't see him from the waist down. But it was clear that he wasn't walking easily and freely at that point.

His favorite recreation was sailing, which of course you sit down while you're sailing. And again, he looked very outdoorsy, very healthy, in that respect. He had been a very agile, healthy person before that—one of the better golfers, for instance, who became president. He actually had a small golf course made for himself that he could golf in in his wheel chair for a while. But he projected an image of being able to move around, not being limited. I think that was the main issue.

I think he's disguising his disability; he made a great effort not to draw attention to it. His press secretary, whenever he was asked about it, would just say it's not a story. The Democrats had actually prepared a pamphlet in defense of Roosevelt about his health conditions to put out if it became a public issue [but] they never released it during the campaign. The Republicans and just his general opponents—and that included Democrats who ran against him for the nomination—they conducted a whispering campaign about Roosevelt. A lot of the whispering campaign was, "Well, it's not really polio, it's really syphilis!" or "it’s a mental illness," or "it’s a stroke," like Woodrow Wilson. They had terrible scenarios that were spread around and there were lots of rumors. So one reason why Roosevelt was out being vigorous in his campaign was to dispel those rumors.

Again, the fact is, anybody who was aware what the—had been reading the newspapers at all in the 1920s and 1930s was not surprised about the news that Roosevelt had polio or that he didn't walk easily. But Roosevelt went to great lengths to minimize that; for instance, at his inauguration there was a viewing stand and they created a chair for him—which was a long pole with a seat—so that he could appear to be standing up for hours while watching this, [but] he was actually sitting down. That was part of the image that he was projecting.

People pose for photographs, this is a posed photograph: Roosevelt is looking "presidential," Eleanor is looking in despair, poor Jimmy is looking a little nervous in the process, and Mark Trice is scared to death. You can just sort of see there all four of them in that image there.

Flickr

Flickr is an online photo management and sharing application. It allows you to upload photos and share, edit, organize, and geotag them, as well as create your own galleries and develop image-based projects. Flickr Commons, a Flickr subgroup, provides access to publicly-held photography collections of museums, archives, and art galleries around the world for public use and comment. Helping students understand the various licenses under Creative Commons is an excellent way to foster discussions on copyright issues—helpful as students progress to college.

Flickr, then, is a valuable resource for educators as they teach subject area content, digital literacy, critical thinking skills, and ideas such as "intellectual property."

Signing in to Flickr is easy. You can use either create a Yahoo account to create a user name and ID, or sign in with a Facebook or Google account. The Flickr Tour offers clear instructions for uploading, editing, organizing, and sharing photos as well as for integrating Flickr with mapping tools and for using it to create projects. Users can also stay up to date with the latest developments via the Flickr blog. Also, for a quick fix on the Flick search function, check out Find Pictures with Flickr on YouTube, a one-and-a-half minute video. Flickr Tutorial Basic Tools, also a YouTube video (it's about seven-and-a-half minutes long), gives more detailed examples of basic Flickr processes you'll need for the classroom: advanced search, Creative Commons, uploading and downloading, how to add notes, and how to create photo sets.

One of the best uses for Flickr in the history classroom is the gallery feature: a "curator" experience that allows users to comb through Flickr's millions of photos in order to create a photo collection. In addition, users can collect images across the internet, upload them into Flickr, then use those photos in the creation of the gallery. Regardless, curating a photo exhibit is an excellent opportunity to work with students on photo selection. Educators can also pose questions that encourage students to asses their own thinking: Why choose this photo, and not that one? Why settle on 10 pictures and not five, or 15? Did you use images that are in the public domain, or copyrighted? Does it matter if you find out that this photo was staged?

Raising questions about intellectual property and copyright with students—particularly the history and court cases related to these topics—is a very useful discussion as they prepare to enter careers or further their education on a college campus. Discussing photo selections can also greatly enhance the teaching and learning of history by forcing students to pay attention to the details of an image, and perhaps to investigate its origin in order to contextualize it. In this quickly constructed gallery of U.S. Presidents, a simple question asks "What do these official, and unofficial, portraits of 10 U.S. Presidents reveal to us about American society?" Here, teachers can construct a gallery and model for students two concepts: photo selection and inquiry-based learning through visuals. Attached to some pictures are some leading comments or directions that can further students' own thoughts as they tackle the main question at hand. In the comments section at the end of the gallery, students can post their response to the question (Note: To post comments, students would have to login ti Flickr using their Google or Yahoo account.) Teachers would probably be wise to think about ways to avoid repetitive answers, such as allowing students to pick a few of the pictures, creating two smaller galleries to split among students, or simply by creating alternate questions for student groups. After modeling and discussing a particular gallery, teachers can then assign each student to curate their own gallery, provide information per image, and ask students to leave comments on each other's products. The "student-as-a-museum-tour guide" approach is an excellent exercise that stimulates higher-order thinking, creates dialogue, and can deepen historical understanding.

Another good collection of sites for visual literacy is found at JakesOnline.

More information on Visual Teaching Strategies can be found here

Explore more on the Flickr Educators Discussion Page

There are also plenty of other ideas that can be incorporated into the history classroom from other disciplines. And for more on copyright and photographs, try our blog entry and Ask a Digital Historian on the subject.

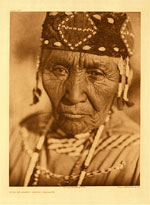

Edward S. Curtis's The North American Indian

More than 2,000 photographs, taken by Edward S. Curtis for his work The North American Indian, are presented here. These striking images of North American tribes are considered some of the most significant representations produced during a time of rapid change, can be browsed by subjects such as persons, custom, jewelry, tools, and buildings. Each image is accompanied by comprehensive identifying data and Curtis' original captions. The voluminous collection and narrative are presented in twenty volumes. Photographs can be browsed by subject, eighty American Indian tribe names, and seven geographic locations. This site also features a twelve-item bibliography and three scholarly essays discussing Curtis' methodology as an ethnographer, the significance of his work to Native peoples of North America, and his promotion of the twentieth-century view that American Indians were a vanishing race. The biographical timeline and map depicting locations where Curtis photographed American Indian groups are especially useful.

Taking the Long View: Panoramic Photographs, 1851-1991

Nearly 4,000 panoramic photographs of cityscapes, landscapes, and group portraits, deposited as copyright submissions by more than 400 companies, are displayed on this site. Panoramic photographs were used to advertise real estate and to document groups, events, and gatherings. Images depict all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and more than 20 foreign countries and territories. Subjects include cityscapes, landscapes, group portraits, agricultural life, disasters, education, engineering, fairs and expositions, industrial scenes, military activities, performing arts, sports, and transportation. Although the images cover the period from 1851 to 1991, the collection centers on the early 20th century. The site includes a bibliography, an illustrated 1,000-word background essay on the history of panoramic photography, and an essay outlining the technicality of shooting a panoramic photograph. Four essays focus on specific photographers: George R. Lawrence (1869–1938); George N. Barnard (1819–1902); Frederick W. Brehm (1871–1950); and Miles F. Weaver (1879–1932).

Touring Turn-of-the-Century America

The Detroit Publishing Company mass produced photographic images—especially color postcards, prints, and albums—for the American market from the late 1890s to 1924. This collection offers more than 25,000 glass negatives and transparencies and about 300 color photolithographs from this company. It also includes images taken prior to the company's formation by landscape photographer William Henry Jackson, who became the company's president in 1898. Jackson's work documenting western sites influenced the conservation movement. Although many images were taken in eastern locations, other areas of the U.S., the Americas, and Europe are represented. The collection specializes in views of buildings, streets, colleges, universities, natural landmarks, and resorts, as well as copies of paintings. Nearly 300 photographs were taken in Cuba during the Spanish-American War. About 900 Mammoth Plate Photographs include views of Hopi peoples and their crafts and landscapes along several railroad lines in the 1880s and 1890s.

Nineteenth-Century American Children and What They Read

This site is devoted to the examination of 19th-century children in America: what they read, what was written about them, and what was written for them. "Children" includes letters, adoption advertisements, paper rewards for obedient children, 24 contemporary articles for and about children, and 14 photographs, as well as scrapbooks and exercise books. "Magazines" features illustrations, articles, editorials, and letters from 12 different children's magazines, with cover and masthead images from 173 different volumes. "Books" includes 22 articles on children and reading (including one warning children to avoid mental gluttony by not reading too much), and the full text of 29 books, including the American Spelling Book and grammar primers. Although the site is not searchable, the documents are indexed and arranged by subject. The site includes eight analytical essays written by modern scholars, a timeline covering the years 1789 to 1873 (with entries covering subjects like magazines, books, historical events, and people), and eight separate bibliographies. A "puzzle drawer" includes word games played by 19th-century children.

Photographs from the Chicago Daily News: 1902-1933

More than 55,000 photographs taken by staff photographers of the Chicago Daily News during the first decades of the 20th century are available on this website. Roughly 20 percent of the photos were published in the paper. The Chicago Daily News was an afternoon paper, sold at a cost of one cent for many years, with stories that tried to appeal to the city's large working-class audience.

The website provides subject access to the photographs, which include street scenes, buildings, prominent people, labor violence, political campaigns and conventions, criminals, ethnic groups, workers, children, actors, and disasters. Many photographs of athletes and political leaders are also featured. While most of the images were taken in Chicago and nearby areas, some were taken elsewhere, including at presidential inaugurations. The images provide a glimpse into varied aspects of urban life and document the use of photography by the press during early 20th century.

Small-Town America: Images from the Robert Dennis Collection, 1850-1920

More than 12,000 stereoscopic photographs depict life in small towns, villages, rural areas, and cities throughout New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut from 1850 to 1920 on this website. Materials include pictures of buildings, street scenes, natural landscapes, agriculture, industry, transportation, homes, businesses, local celebrations, natural disasters, and people.

Each grouping of photographs offers a short description of the contents as well as notes on the locations, medium, collection names, and digital identification information. The site also features an essay on the history of stereoscopic views and nine related website links. The site is searchable by keyword and can be browsed by subject and image name. These revealing illustrations are valuable for examining rural and urban development as well as everyday life.