Mary Hendrickse: We're going to start off with a really simple activity—the Coke bottle—and finding out how much information we can get about Coca-Cola from this Coke bottle.

Speaker 1: I notice that the shape is made to feel good as you're holding it.

Kendra Huffbower: I notice that it's made out of glass, so it could be recycled…

Kendra Huffbower: The Coke bottle we were thinking about incorporating into our daily morning meeting routine. Where that's kind of the activity and you pass an object and you really have to think about what they're noticing and why they're noticing that and how it's used and the function and design of it.

Speaker 2: There's another image on here. There's an image of a Coke bottle printed on the Coke bottle. Maybe that's something to do with scanning or something?

Speaker 3: Yeah, going on the shape of it, it's kind of…seeing that it comes out of the 1950s-ish time, it's kind of got an hourglass shape of a slender woman's body.

Speaker 4: That was mine! No!

Speaker 3: But that's good, great minds think alike! It reminds me of Barbie or something.

Mary Hendrickse: Okay, okay, so the hourglass figure type of idea.

Speaker 3: Whether that was implicit or not.

Mary Hendrickse: Why do you think—let's just go with that.

Speaker 4: Can I tell why, 'cause that was my thing?

Speaker 3: This was a joint thing between minds.

Mary Hendrickse: Why do you think they might have used that shape, that hourglass shape?

Speaker 4: I think it's advertising, because if I drink it I'm gonna look like Barbie.

Speaker 5: It has a date on it—11 February 12. I'm assuming it's either expiration date or…

Mary Hendrickse: If that is the expiration date, what do we think about that? That it expires next year, like eight months from now.

Speaker 6: Lots of preservatives.

Mary Hendrickse: Lots of preservatives, okay.

Speaker 2: That it has an expiration date, though, at all. That's better than if it doesn't!

Rachel Blessing: We talked a lot about visual literacy today and trying to incorporate that in a meaningful way in the classroom is my hope. I've been writing down how she's [Mary Hendrickse] been teaching us, because that's something that she's modeling for us. I don't know if she knows that, but she is.

Rachel Blessing: It's from Mexico.

Mary Hendrickse: Okay, it was made in Mexico. So what does that tell us?

Kendra Doyle: I think sometimes we can just get so caught up in day-to-day things that we don't take the time to look at the outside of a building and just see what does this tell us, what does this mean? Taking the time to just slow down and observe and analyze, that’s something that I've learned.

Kendra Doyle: I noticed the label, it's red, and the way the Coca-Cola is written it looks like a ribbon almost, the script. It's like a repeating sound, it's like a catchy sound—Coca-Cola—it's like the same letters.

Mary Hendrickse: So, I wanted to point out that it took us one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight, nine, 10, 11, 12, 13 people to get to the logo that's written on it. Because that's something that we expect to see, so we don’t really think about it very often.

I have some disks that I'll give you at the end of the day in an electronic form so you can use it again if you want to and it's got the reason behind some of the design parts. They did go for the curvy bottle on purpose, for both easy gripping and attractiveness—because it looked like a woman—and the red and white because it was bold colors. So there's a reason behind even the smallest details of a Coke bottle, and the same thing goes with buildings. Even the smallest detail in a building has importance and has meaning.

Mary Hendrickse: Visual literacy is really about slowing your students down and asking them to articulate why they are making the assumptions they are. What did they see that makes them say that? We're very quick to say, "Oh, that's a school." Well, why does it look like a school? What about it makes it look like a school? It's about looking closer and longer and further. Drawing is one way that you can do that. It's also important to ask questions that bring you to more questions and more ideas. And it's also important to get your kids to ask questions too.

There's a handout over there called "50 Ways to Look at a Big Mac Box." These are good questions to use about anything. You can use them about a Coke bottle, you can use them about a building, you can use this as a reference. I'm going to give each group two pictures of buildings you may not be familiar with. You can either work on them together, you can pick one to work on as a group, or you can split up into two smaller groups. I would like you to use those questions and look really closely at the details to see if you can figure out more information about this building. Okay? Does that make sense to everybody?

[Group 1:]

Speaker 1: That's the entrance.

Speaker 2: And are these windows?

Speaker 1: Ah, could be, letting in some light.

Speaker 2: Or ventilation.

Speaker 3: So describe the shape—

Speaker 2: Yeah, I would say planetarium or an arena.

Speaker 4: I was thinking like a rec center.

Speaker 1: Yeah, a sports center.

[Group 2:]

Speaker 1: We said that we noticed the landscape in this one. We noticed the intentional barriers. The park area is set up to where you can enjoy the view of the building and set up to where you might want to just go and take a walk.

Speaker 2: There's shade because there's trees; if it's sunny you can do a picnic underneath them.

Speaker 3: And I think that's juxtaposed with the symmetrical almost like prism, to me, structure.

Speaker 1: The straight lines.

Speaker 3: It's straight, the windows are tiny and narrow and dark.

[Large-group discussion:]

Mary Hendrickse: We're going to go around and I'd like each group to tell a little bit about what they think about these buildings. What did you…what do you think about this one?

Speaker 1: The design is different. When you look inside of it, it looks kind of like the chandelier crystal things hanging down. The top looks very translucent. We were kind of thinking if it's like a memorial type thing.

Speaker 2: There's a variety of materials because the bottom level is like these pillars but glass in the front and in the back, and then there's this marble layer. We can't really tell what exactly the material is at the top, but it's like this mesh, it looks like a metal sort of mesh glittery something.

Speaker 3: And when you look up through the center of the building, you can see it glows a little bit, almost like it's open. So there's offices or some functioning room up top.

Mary Hendrickse: Okay, yeah, absolutely. So this is one proposed design for the National Museum of African American Culture and Heritage. You guys were absolutely on target when you were thinking about what the different parts mean. The design was supposed to look like a crown—this idea of a crown—it was supposed to look like it glows. I mean, you guys were able to get a lot of information out of this just by looking at it.

[Group 3:]

Speaker 1: See what the people are wearing.

Speaker 2: See what the people are wearing or doing.

[This seems odd…should this group discussion be here?]

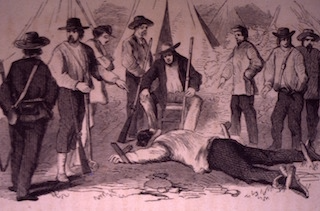

Mary Hendrickse: This building was built a long time ago to be both a Pension Bureau for Civil War soldiers so they could come in and pick up their retirement checks or pensions, and also a space to have inaugural balls. As we're going through we're going to be drawing things and looking at different aspects of the building and seeing how they can reveal different information about how this building was used.

Rachel Blessing: I can't tell you the last time I've drawn a picture, so just being forced to do those things and remembering what it's like for the kids, and also just learning new things. I grew up in DC, and I've been to this building but I didn't know half of what I learned today.

Speaker 1: Look, there's a clue. There's a Civil War clue right there. There's people coming to get their pensions.

Mary Hendrickse: The first thing that I want you to do is to open up your sketchbooks. We are going to do a 30-second quick sketch. I want you to get a sort of big picture, overall impressions of what you see in this space, okay? What were you able to capture in 30 seconds?

Multiple Speakers: Nothing. Columns. Arches.

Mary Hendrickse: Okay, so columns, arches. So maybe something that the architect really wanted you to look at and focus on when you came into the building. What about those arches and columns? What do you notice about them?

Speaker 2: They look like aqueducts.

Mary Hendrickse: They look like aqueducts, okay. Aqueducts from today or from—

Speaker 3: No, like Rome.

Mary Hendrickse: Okay, so like the Roman aqueducts.

Kendra Doyle: Ancient Greece and Rome—what connection does it have to that? What message are they trying to send? So I think being here sometimes reinforces some of those ideas about those things we've discussed in class.

Mary Hendrickse: What is this?

Multiple Speakers: It's the seal.

Mary Hendrickse: It's the seal. The seal of what?

Multiple Speakers: The United States of America.

Kendra Doyle: We might be able to actually do a field study to a site. If not, we also discussed just starting by analyzing the buildings that we're in. So many DC schools have this history and if we just take the time to look at what's around us, the buildings themselves tell an important story.

Mary Hendrickse: Doesn't have to be perfect, you're just recording clues. Your own interpretation of what you see.

Judy Leek Bowers: Drawing, I thought that was neat, because then you really do get to see what different people think is important. None of our drawings were the same.

Mary Hendrickse: We're going to do a really quick share; this is the easiest way to share. Everybody hold up your sketchpads like this. There you go. Take notice of what other people have drawn. Did they draw things that are similar to you? Different?

Speaker 1: Yeah, I did. I don't see what other people see.

Judy Leek Bowers: There's always a new technique. There's always somebody that you meet that has a different perspective. In just this short length of time it's opened my eyes to other ways to address the children. Really having more instruction that's almost individualized to each child so that they can think more deeply about the place and the power it might have.

Mary Hendrickse: What were some of the things that people drew?

Multiple Speakers: The doorway.

Speaker 1: The columns.

Mary Hendrickse: What can the door tell you about how the building was used? Is it like a normal door you would see on a house? How else is it different from a normal door?

Speaker 2: It's huge, it's inviting. The window above it at the same time—it's not a stained glass window, but still you [can] see an old castle or church.

Mary Hendrickse: It's a little bit elaborate; it's not really a plain door.

Speaker 3: What about the sculpture around the door? It's so different from that.

Mary Hendrickse: The sculptures around the door. Anybody want to guess who those people might be?

Speaker 4: You've got different ones. You have the Navy kind of on this side and then you have the Army maybe on this side.

Mary Hendrickse: We know it's from the Pension Bureau, so these were some of the people who were going to be coming into the building. So they had a visual clue on the outside of the building about what this building was used for.

Mary Hendrickse: Let's start off with the Capitol Building. Who was looking at the Capitol Building?

Speaker 1: The fact that there's the two houses—Senate and the House of Representatives—kind of link this idea of states and the nation, and then the dome in the middle kind of unifies the two. There's the Greek-style columns, which pay tribute to the birthplace of democracy.

Speaker 2: Everything else paled in comparison; the marble, the white symbolized purity.

Mary Hendrickse: Ideal, pristine, we're doing good things here. Perched upon the hill to add to the importance.

Speaker 1: Stately, powerful in itself; but not overdone, not overblown, not too elaborate.

Mary Hendrickse: A house for the president rather than a mansion for the president, or a castle for the president. So not towards the realm of king and royalty, but still important enough that a president can live in there.

Speaker 2: It's got kind of a plantation house feel to it, too.

Mary Hendrickse: Anything else that anybody wanted to add? We still have that continuation of the white coloring again and that reference to classical architecture with the columns and the capitals.

Mary Hendrickse: Who looked at the Jefferson Memorial?

Speaker 1: We talked about the columns and the architecture, the structure of the building being reminiscent of ancient Roman architecture and how Rome was the greatest power of its time so it's our expression of being one of the greatest powers in the world.

Speaker 2: We also talked about him standing as opposed to Lincoln, who is sitting.

Mary Hendrickse: What did you think about him standing?

Speaker 3: He was sort of presiding over everything and the idea that when you go to the monument you have to walk up the steps to greet him and you have to look up at Jefferson; and he's just sort of looking down—not looking down on us, but—

Mary Hendrickse: Surveying the land?

Speaker 3: Right. But just sort of overseeing, making sure the democracy stays intact.

Mary Hendrickse: Okay, the Lincoln Memorial. Who was looking at that one?

Speaker 1: We talked about the Parthenon and the Greek influence.

Mary Hendrickse: Anything else? What about the size of Lincoln? He's huge! So what does that say?

Speaker 3: He's a huge figure in American history

Speaker 4: He has a huge position in our history.

Mary Hendrickse: Okay, so his position in our history, he's this huge man, huge figure in our history. The original statue was going to be a lot smaller and then when they went to start trying to figure out putting it in the building they realized it was going to be much too small and it would be dwarfed by the architecture, so they made it even bigger.

Speaker 5: I always think it's so ironic to think that they ended up making this huge statue of him and making him this huge icon, whereas what we know of him and his personality is so humble and, you know, just your everyday man. I just only imagine what he would think if he could see this.

Mary Hendrickse: It's got symbols on it about Lincoln, but the building itself has become a bigger symbol for civil rights and for rights in general. It's grown beyond what Lincoln was about to be even more symbolic and meaningful to the country.

Speaker 6:: So don't meanings always evolve? The meanings of the power of a place always is changing.

Mary Hendrickse: Absolutely, these things grow, you're absolutely right. They grow and they evolve until what we think now about the Lincoln Memorial is not the same thing they would have thought about the Lincoln Memorial in the 1920s.

Judy Leek Bowers: I'm understanding that everything that's historical is not written. Some things are based on the boulder that's in the middle of the road and it has a story behind it. Why is it significant in the District of Columbia, and why is it significant to you? And that's where I need to learn to make the connection for the students. Who really decides if the place has power?

Don't miss our

Don't miss our

Have students search for topics both historical and contemporary, and see what the entries for the images they turn up say about copyright. "No known restrictions on publication?" "Unrestricted?" Images created before 1923 should be in the public domain, free of copyright restrictions, as should images created by government organizations. More recent sources may note copyright restrictions, including specific caveats about how a source may be reproduced.

Have students search for topics both historical and contemporary, and see what the entries for the images they turn up say about copyright. "No known restrictions on publication?" "Unrestricted?" Images created before 1923 should be in the public domain, free of copyright restrictions, as should images created by government organizations. More recent sources may note copyright restrictions, including specific caveats about how a source may be reproduced. Another informative stop might be Yahoo's

Another informative stop might be Yahoo's  Now that your students understand how tricky it may be to find sources that can be freely used to tell the story of history, they're in a position to help out, themselves! What historic sites or other traces of history exist in your local area? Are there Creative Commons-licensed images of these on, say, Flickr? If not, how about collecting some? Students can help fill in the gaps in our public record of place and time, and add to the resources available to students like themselves.

Now that your students understand how tricky it may be to find sources that can be freely used to tell the story of history, they're in a position to help out, themselves! What historic sites or other traces of history exist in your local area? Are there Creative Commons-licensed images of these on, say, Flickr? If not, how about collecting some? Students can help fill in the gaps in our public record of place and time, and add to the resources available to students like themselves.