The summer of 2011 offers moviegoers several productions based on superheroes and comic books. Thor. X-Men: First Class. Green Lantern. Captain America: The First Avenger. Cowboys & Aliens. Hollywood has discovered that comic book movies are more than a passing fad, resonating with audiences who connect with the humanity behind the costumes. As a result, comic book-based films have grown over the last decade—both in production and ticket sales— with many more movies to be released over the next few years (The Dark Knight Rises, The Amazing Spider-man, Iron Man 3, and The Avengers to name a few.)

Teachers can use the popularity of superhero films to expand students' understanding of American culture. University of Idaho professor of history Katherine Aiken explored the use of comic books to teach U.S. history in a recent essay published by the Organization of American Historians' Magazine of History (Vol.24, no.2-April 2010). Aiken concluded that because comic books reflect larger social issues in U.S. society, they can help students examine how U.S. artists addressed issues of race, gender, nationalism, and conflict in popular publications.

Some educational publishers, for their part, have produced illustrated history stories and graphic novels to capture younger readers' attention, such as tales from the Revolutionary War. While history-based graphic novels are a useful supplement to course materials, studying comic books provides a different focus in the classroom. Analyzing U.S. popular culture can help teachers and students contextualize the origins of comic books, explore how events in history shaped the evolution of this medium, and assess the ability of comics to address larger social concerns.

A few approaches for connecting comic books to U.S. history include:

- Chronological comparative study

Students can create timelines, decade-level synopses, or graphic organizers that align U.S. historical events with the dates of creation of specific comic books, and show how these titles reflected social concerns. (For a nice overview on the history of comic books, Michigan State University's Ethan Wattrell's course website contains lecture slides and podcasts that can help orient educators.)

For example:

- 1920–30s: Comic books developed as a form of fantasy and escapism during the 1920s and the Great Depression.

- 1940s: Superheroes went to war. Did comic books become tools for wartime propaganda, or did they simply reflect a period of national pride?

- 1950s: Fantasy, horror, Westerns, and other genres overshadowed superhero stories. Is this a case of "hero" fatigue or socio-political concerns?

- 1960s: The Marvel and Silver Ages: The Cold War, space race, and civil rights shaped a new era of heroes. The space race, for example, influenced the creation of the Fantastic Four and other interstellar heroes. The nuclear arms race, in turn, influenced the creation of Iron Man and the Hulk. Civil rights also played a significant role in the development of characters with social struggles, from the mutant X-Men to the blind superhero known as Daredevil and the increasing number of female heroines beyond Wonder Woman.

- 1970s–1980s: Comic books became more mature. Serious issues such as drug abuse and apartheid influenced storylines in teen-centered titles such as the Teen Titans and X-Men/New Mutants. Specific stories, such as The Dark Knight Returns and Watchmen, tapped into the economic and political anxieties during the Reagan era. Titles such as Sandman also introduced comic books to a new generation of female readers during the late 1980s. All three titles appeared on the New York Times Bestseller list.

- Addressing social issues

Popular culture has often been able to deal with serious issues in an accessible manner. The story of Genosha in the pages of the X-Men extended the theme of genetic discrimination against mutants to issues of slavery and oppression—much like apartheid in South Africa. In this vein, comic books are an accessible way to address other social issues.

For example:

- Gender studies: How did the feminist movements of the 1970s affect characters like Wonder Woman and the Invisible Girl/Woman? What changes are visible in the depiction of female superheroes? How has the growing visibility of female artists, such as Louise Simonson, Lynn Varley, and Gail Simone, changed a male-dominated industry?

- Activism: Students can study the effects of larger events such as the Vietnam War, September 11th, and the passage of the Patriot Act on comic book storylines. Recent stories such as Marvel's Civil War and World War II-era comics are useful starting points to examine individual rights and nationalism respectively.

- Intellectual Property: Why was DC Comics unable to use the names "Superboy" and "Captain Marvel?" How did the founding of Image Comics become a significant development for independent comic books and the idea of creator rights? How do copyright and fair use laws affect the use of comic book characters in education?

- "Golden Age," "Silver Age," and "Modern Age" of comic books

What characterized each of these eras? Using long-running characters like Batman and the Joker, students can assess changing social norms, expectations, and trends in the 20th-century U.S. through the evolution of specific characters.

- Government regulations and political concerns

McCarthyism and moral issues threatened the comic book industry during the 1950s. Why? One fascinating story involves Fredric Wertham's Seduction of the Innocent, a bestselling book that eventually led to the policing and regulation of comic books and the creation of the Comic Code Authority. This is a good period to discuss government regulations, free speech, and what made comic books a "danger" to children in the 1950s. Another topic, dealing with moral issues, is human experimentation. In this video by Emory Bioethics professor Paul Root Wolpe, he uses the genetics in the X-Men comic books to talk about Nazi experimentation on humans, the Nuremberg trials, as well as U.S. testing on human subjects.

- The evolution of major characters

While Batman is one of the easiest character to compare his own evolution to changes in American society, he is not the only one that shows the influence of time and place. Tony Stark (Iron Man) famously struggled with alcoholism in the 1980s. Captain America went from World War II hero to a man out of time after decades of frozen animation. Peter Parker's (Spider-man) journey from awkward teenager to a married professional may be an easy-to-relate-to story for students. Likewise, Superman's recent decision to forgo his American identity, in order to embrace a more "global" role, created renewed interest (and a bit of controversy) in the media.

- Comic book creators

How did the personal lives of writers and illustrators like Stan Lee, Jack Kirby, Jerry Siegel, and Joe Schuster, among others, affect the tales they created? Many of these artists came from ethnic and working-class communities that shaped the setting and topics of their stories.

Comic books, therefore, can help diversify the teaching of American history and allows teachers to address important issues in a novel yet useful way. However, educators should take caution. Over the last few decades, comic books have shifted to a more mature audience and as a result the depiction of violence has become more graphic. Similarly, educators should be mindful of issues or artists that oversexualize characters.

Comic books, therefore, can help diversify the teaching of American history and allows teachers to address important issues in a novel yet useful way. However, educators should take caution. Over the last few decades, comic books have shifted to a more mature audience and as a result the depiction of violence has become more graphic. Similarly, educators should be mindful of issues or artists that oversexualize characters.

As is the case with any material to be used in the U.S. history classroom, comic books should be previewed beforehand. Educators, however, can find plenty of "classroom-friendly" comics online or at a local comic book store. For example, the Pulitzer Prize-winning comic, Maus, commonly found at most school libraries, is a different take on Nazism and the Holocaust. Comic book companies have also increased their number of "kid-friendly" titles, easily found at bookstores like Barnes & Nobles and department stores such as Target. Finally, the first Saturday in May is "Free Comic Book Day" each year—a good chance to explore several titles at a local comic book store.

A final note:

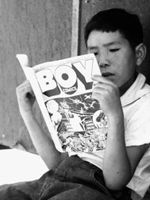

Interdisciplinary approaches to using comic books in the classroom are also helpful for the history teacher. Art educators often argue that reading and making comics encourages students to become more skilled at critically examining texts—full of complex concepts and human relations. Students and teachers can use comics to bridge the gap between personal experiences and history, examine the connection between comics and social groups (such as the "art world" and ethnic groups,) and to deconstruct the medium in order to gain a better sense of what issues affected society. The marriage of visuals and text also helps reach reluctant readers and bring the classroom teacher closer to youth culture. Similarly, language arts specialists find that engagement enhances reading fluency— even in the elementary years. Low-level readers, in various studies, demonstrate greater engagement with visual texts like comic books.

Interdisciplinary approaches to using comic books in the classroom are also helpful for the history teacher. Art educators often argue that reading and making comics encourages students to become more skilled at critically examining texts—full of complex concepts and human relations. Students and teachers can use comics to bridge the gap between personal experiences and history, examine the connection between comics and social groups (such as the "art world" and ethnic groups,) and to deconstruct the medium in order to gain a better sense of what issues affected society. The marriage of visuals and text also helps reach reluctant readers and bring the classroom teacher closer to youth culture. Similarly, language arts specialists find that engagement enhances reading fluency— even in the elementary years. Low-level readers, in various studies, demonstrate greater engagement with visual texts like comic books.

History teachers can benefit from collaborative uses of comic books across disciplines. Either by working with a language arts or art teacher, or adapting diverse approaches to visual literacy in the history classroom, the use of comic books is helpful for working with others. Students will also find similar collaborative benefits in outside research and work. Whether they develop digital timelines using tools like Dipity or generate a Google Map to assess the geographic connections of comic book characters to U.S. history, digital tools are ideal for collaborations inside and outside the classroom. (Note: The Dipity and Google Map links show examples of how to use American comic books to teach U.S. History.)

History teachers can benefit from collaborative uses of comic books across disciplines. Either by working with a language arts or art teacher, or adapting diverse approaches to visual literacy in the history classroom, the use of comic books is helpful for working with others. Students will also find similar collaborative benefits in outside research and work. Whether they develop digital timelines using tools like Dipity or generate a Google Map to assess the geographic connections of comic book characters to U.S. history, digital tools are ideal for collaborations inside and outside the classroom. (Note: The Dipity and Google Map links show examples of how to use American comic books to teach U.S. History.)

Comic books, therefore, can help diversify the teaching of American history and allows teachers to address important issues in a novel yet useful way. However, educators should take caution. Over the last few decades, comic books have shifted to a more mature audience and as a result the depiction of violence has become more graphic. Similarly, educators should be mindful of issues or artists that oversexualize characters.

Comic books, therefore, can help diversify the teaching of American history and allows teachers to address important issues in a novel yet useful way. However, educators should take caution. Over the last few decades, comic books have shifted to a more mature audience and as a result the depiction of violence has become more graphic. Similarly, educators should be mindful of issues or artists that oversexualize characters.  Interdisciplinary approaches to using comic books in the classroom are also helpful for the history teacher. Art educators often argue that reading and making comics encourages students to become more skilled at critically examining texts—full of complex concepts and human relations. Students and teachers can use comics to bridge the gap between personal experiences and history, examine the connection between comics and social groups (such as the "art world" and ethnic groups,) and to deconstruct the medium in order to gain a better sense of what issues affected society. The marriage of visuals and text also helps reach reluctant readers and bring the classroom teacher closer to youth culture. Similarly, language arts specialists find that engagement enhances reading fluency— even in the elementary years. Low-level readers, in various studies, demonstrate greater engagement with visual texts like comic books.

Interdisciplinary approaches to using comic books in the classroom are also helpful for the history teacher. Art educators often argue that reading and making comics encourages students to become more skilled at critically examining texts—full of complex concepts and human relations. Students and teachers can use comics to bridge the gap between personal experiences and history, examine the connection between comics and social groups (such as the "art world" and ethnic groups,) and to deconstruct the medium in order to gain a better sense of what issues affected society. The marriage of visuals and text also helps reach reluctant readers and bring the classroom teacher closer to youth culture. Similarly, language arts specialists find that engagement enhances reading fluency— even in the elementary years. Low-level readers, in various studies, demonstrate greater engagement with visual texts like comic books.  History teachers can benefit from collaborative uses of comic books across disciplines. Either by working with a language arts or art teacher, or adapting diverse approaches to visual literacy in the history classroom, the use of comic books is helpful for working with others. Students will also find similar collaborative benefits in outside research and work. Whether they develop digital timelines using tools like

History teachers can benefit from collaborative uses of comic books across disciplines. Either by working with a language arts or art teacher, or adapting diverse approaches to visual literacy in the history classroom, the use of comic books is helpful for working with others. Students will also find similar collaborative benefits in outside research and work. Whether they develop digital timelines using tools like