The first source is by Frederick Law Olmsted, published in a collection called The Cotton Kingdom, in 1861. Olmsted was an eclectic man to be sure. He was an agricultural journalist, he was a landscape architect. He designed New York Central Park. But in 1853 he was commissioned by the New York Times to conduct a number of investigative tours through the American South and the slaveholding states of that region.

Over the course of the next 18 months he toured practically every part of the American South, compiling reports, sending them to the Times, and publishing them. And his intention was really to give Northern readers, who had no sense of the region of the Southern states and no sense of slavery, to give them an "authentic," in inverted commas, impression of what slavery was like.

The second source is by Solomon Northup, and Northup is an absolutely fascinating man. He was born free in Saratoga Springs, in New York, whose mother was of mixed-race origins, but importantly, Northup was a free man. In 1841 he is kidnapped, and he is sold into slavery in Washington, DC. He was transported south, and he was then sold to a number of different planters in central Louisiana, particularly on the Red River. Finally, after 12 years in bondage, Northup encounters a Canadian, a Canadian carpenter, who is anti-slavery himself, and it is that carpenter who writes letters north to—back to Saratoga to achieve and to require legal documentation that Northup was indeed a free man, and indeed, at that point he is finally liberated.

And one of the problems of writing history, and teaching history in point of fact, is: How do we recover the slave's voice? How do we recover those who actually were there? What did they think? What did they feel?

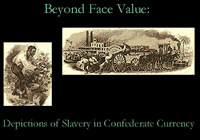

These products, these slave-written products, often published with the assistance of the abolitionists, represent one version of slavery. Olmsted represents another version of slavery. If we were to go to a plantation, archives in Georgia, Louisiana, across the American South, you'd read documents written by the slaveholders themselves. None of these versions are authentic in and of themselves. It is the task of the historian to essentially read against the grain of these documents, to push them back, to see what is probable, what is hidden, so that we assess these various documents in tandem, until collectively they represent a version that we might call the nearest to the facts of American slavery.

Both documents are suffused with 19th-century text. They're melodramatic, they're in one sense romantic. But they represent wholly different impressions, and this is really the nature of slavery. If you read, for example, Olmsted's account, it appears that the masters and the slaves seem to have a relatively good relationship. There's a sense of a kind of intimacy within the plantation world.

By contrast, if we pick up Northup's account, Northup's account is suffused with violence. It's suffused with the realities from the African American perspective, the realities of slaveholding, the realities of life in bondage.

When we look at Olmsted, we look at the way in which slaveholders manipulate the slave system. They provide the African Americans with absolutely nothing within the plantation and they make them use any money that they earn on Saturdays or Sundays to pay for the most modest of additional items: slightly improved food, plates, cups, the very raw products of life in a clapboard shack. Solomon Northup, of course, alludes to the fact that how significant this money becomes, that even though it is very small, the amount of money that is accrued by African Americans by Sunday trading, to those people in chains, the significance of purchasing cups, pails, calicos, of a very constrained commercialism, of a very limited commercialism, that for those people, that's enormously significant, the idea of ownership, of anything in a system that denies fundamental ownership.

If you put it in contrast to Olmsted, they look like completely separate regimes. They look like completely separate worlds, and it's the task of the historian to essentially place those two perspectives together and to tease out—Olmsted represents very much what planters wanted to think of the regime; Northup very much what slaves experienced of the regime.

We see a planter, Mr. R, he's probably [Mr. Andre Román], owner of a major plantation on Houmas Band on the Mississippi River in today's Ascension Parish. If we look at his description, Mr. R walks out onto the plantation. He's returned from illness, and he orchestrates this entire visual imagery.

So he marches out and he immediately inquires of the slaves: "Well, how are you girls?" he refers. "Oh"—and there's this immediate repartee between the enslaved and the enslaver, one that appears to be in a sense of mutual interest. But even at this earliest point, the planter is beginning to inscribe his authority.

This really gets to the core of how slaveholders thought of themselves. So he immediately inquires: "How are the children?" and he's very quick to make sure that the children, the sick children, are on the road to recovery. He begins to enforce a visual image of his authority as a slaveholder, and also, this sense that slaveholders had of themselves. And they often describe themselves as standing in pater familias, in replacement to the father.

And again we begin to see this relationship develop as he goes on into the plantation, and he goes out viewing the slaves and goes out making reference to the work. But herein lies the essence of the relationship. He goes to the [fence] he goes to a lad driving a cart, and he pulls out and he pulls up to him. He says, "Well, I'm getting on all right. But If I don't get about and look after you, I'm afraid we shan't have much of a crop. I don't know what you're going to do for your Christmas money."

And this was a tradition very common in south Louisiana, that to make a slave essentially work exceptionally hard, they were rewarded at Christmas, at the end of the harvest, with a small financial token relative to the proportionate size of the crop that they'd cultivated. The planter enforces this idea of his generosity.

But the slave is nonplussed. He's not fooled by this charade that the slaveholder has orchestrated, the showy display of authority that we have just seen with the slave women, now this rather ostentatious expression on the relationship with the young lad in the cart, because the slave returns and says, "Oh, well, you just go on. You just go and look down the field somewhat, and you just go and see what's there." And of course, what the slave is reporting and pointing to is a fine stand of cane in the distance and, importantly, by implication, that the slaveholder will pay the Christmas money and this time, a substantial amount of it.

Slavery is a relationship built on force. It's built on the ownership of one person by another. It's built on the power to compel that work—compel it by extreme physical violence. The slaveholders also knew that under these circumstances they had to combine it with elements of waged work to create what they needed at the end. What they needed was the cane cultivated, the cane cut, the cane ground and processed.

However objectionable slavery is, the slaveholders truly believed this image of themselves. It was a charade. It was deeply objectionable. But it was a way to justify holding other people in bondage. And it's important to say that these are amongst the last slaveholders in the new world. They're standing against time. They're standing against modernity. Only Brazil, only the Spanish Empire, and only the United States by the middle of the 19th century, are slave-holding powers.

Olmsted, however, interviews a African American and what occurs within this context is, we're stripped away from the planter's charade. Instead, we have a one-on-one conversation with a slave by the name of William.

So we learn at the very first instance that he comes from Virginia, and like so many of his compatriots of those slaves who resided in south Louisiana, they were part of the inter-regional slave trade, a movement of slaves from Virginia, Maryland, to the deep south. Hence the expression "sold down the river."

He wants, above all, to return to his family. When he's finally released and he asks "If I was free, if I was free," he indicates one, that he wanted to return to Virginia to see his mother. Secondly, he says what kind of a world he wants to live in, and he says what he wants to do is raise some crops on a little farm, a little land, but land of his own, independent land. And he says he wants to trade them down in New Orleans.

But ultimately, that's his vision of freedom: a restoration of family and independent land ownership. And those things ring absolutely true with what we know of African Americans as they come out of slavery and into freedom, through the Civil War years, and immediately on into the immediate aftermath of reconstruction and emancipation.

So Northup, as we've made reference to, offers almost an entirely opposite perspective to that presented by Olmsted. Olmsted looked at it in terms of these economic incentives, this Sunday money, etc., as a way to cajole the slaves to work even harder. Northup explodes that image here. As Northup observes, in this way only are they able to provide themselves with any luxury or convenience whatsoever.

"When a slave, purchased, or kidnapped in the North, is transported to a cabin on Bayou Boeuf, he is furnished with neither knife, nor fork, nor dish, nor kettle, nor any other thing in the shape of crockery, or furniture of any nature of description. He is furnished with a blanket before he reaches there, and wrapping that around him, he can either stand up, or lie down upon the ground, or on a board."

"To ask the master for a knife, or skillet, or any small convenience of the kind, would be answered with a kick, or laughed at as a joke. Whatever necessary article of this nature is found in a cabin has been purchased," he says, "with Sunday money. However injurious to the morals, it is certainly a blessing to the physical condition of the slave, to be permitted to break the Sabbath."

Here lies the slave's perspective in its rawest form. Here lies not a planter class who is offering some kind of added benefits like better housing, some food, some money or the like, as some kind of generosity. Here it's a cynical, abusive planter class, that essentially denies their slaves every single thing, and makes them—makes the slaves pay for any object.

So I think the first question the students would ask is, "Why are they so different? Why are these accounts so different?" Because they are, and they're not. They describe the same phenomenon, but from two sides of the telescope, if you like. The planter's side in Olmsted, and then the slaves' side—although Olmsted, as we pointed—tries to give this conversation with the slave William as well. So where does reality lie between this image that slaveholders have and this experienced reality that Northup gives?

I think another question that students should want to ask themselves is, "By reading this document, how can we best understand the system of slavery, both as a racial system, as an economic system, and as a system of power?"

Slaveholders wanted to inscribe that authority time and time and time again. Slaves, by contrast, generally speaking, wished to reject that authority. How, then, by reading these documents, do we begin to understand how people thrown together in the American south of the 19th century, both lived and experienced slavery.

The average plantations numbered about 75 slaves. Most plantations numbered much less. The largest number of slaveholders in the American south, the largest number of slaveholders, owned one slave, one or two slaves.

Ultimately, what defines slavery in the American south is a very uneasy, uneasy compromise. An uneasy compromise where unfortunately power does lie, and laid very firmly with the slaveholders, and as Solomon Northup indicates, it rests also with the compulsion of the power of the whip and the power of the slaveholders to enforce their will by violence when they so wished.

Both texts provide a way of understanding this very, very complex, and often extremely violent relationship between blacks and whites in the American south. The texts offer us a way to understand how slavery ultimately worked as a system, how it ended up becoming so profitable as it did.

I think the texts also provide us with a way of examining how American racism will ultimately impinge upon the visions and aspirations of African Americans as they go from slavery into freedom.