The Modern Civil Rights Movement: A River of Purposeful Anger

Did individual African American activists spark the Civil Rights Movement?

Textbooks are silent about defining race and racism, even though the modern Civil Rights Movement and its antecedent movements were efforts to challenge and eliminate racism. Rather than addressing the outrage of systematically being denied basic human rights by the U.S. Supreme Court, while citizens in a democracy, textbooks suggest that individual African Americans were merely sad or angry because individual white people did not want to fight wars, play baseball, learn, ride public transportation or eat lunch with them.

The most important lessons of the modern Civil Rights Movement will not be gained from passively reading textbooks. Examining primary sources will place students closer to the scenes of the modern Civil Rights Movement and its antecedent movements. Too often Dr. King is represented in textbooks as the person who was sent to save African Americans from racism, or the most powerful leader of the modern Civil Rights Movement, or as a political moderate. Instead, he was one of many powerful leaders.

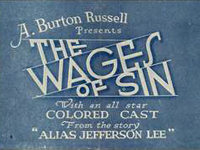

Textbooks define segregation benignly with little reference to the ways in which northern and southern state governments and businesses systematically – and over the course of several decades -- reinforced an ideology of white supremacy through violence. Other groups of people affected by these same laws and practices – including American Indians, Mexican Americans, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, Native Hawaiians, Native Alaskans, Jews and Arabs – are seldom included in textbook discussions of racism. These absences strip away the underlying motivation for collective anger and social action.

Textbooks present the modern Civil Rights Movement in the same way as other U.S. social movements -- a spontaneous, emotional eruption of saintly activists led by two or three inspired orators in response to momentary aberrations in the exercise of democracy. In particular, textbooks imply that, until World War II, African Americans had been relatively content with social, economic, and political conditions in the U.S. Then, suddenly, African Americans were angered that they could not fight on battlefields, play baseball, attend schools, or sit on buses with whites. Further, African Americans were the only people to observe and protest these conditions. Finally, to act on their discontent, African Americans required instructions from a benevolent federal government, or a single charismatic or sympathetic leader. A more accurate telling of the story of the modern Civil Rights Movement indicates that the “river of purposeful anger” has been long, wide and well populated.

The modern Civil Rights Movement is often marked as beginning with the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court decision banning school segregation or the day in 1955 when Rosa Parks refused to move from a bus seat in Montgomery, AL and ends with the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act or with the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1968 (Or, more recently, with the election of President Barack Obama). In some textbooks, the context for this movement are the years following the 1896 U.S. Supreme Court case of Plessy V.