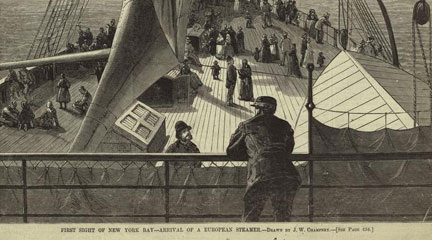

While the story of Jewish immigration to America often begins in the late 1800s, this rich story dates back to the beginning of the nation. We have included this essay in the lesson plan review section because it clearly identifies lesson topics, briefly presents teachers and students with a rich and nuanced overview of Jewish history, and provides resources to further explore the topic. The authors of this essay, Jonathan D. Sarna and Jonathan Golden of Brandeis University, explore how the evolution of Jewish customs and practices in America can be examined under the broad lens of assimilation. One scholarly debate summarized in this essay concerns the role of Old World and New World influences in shaping the distinct Jewish tradition that evolved in America. For teachers wishing to develop a historical inquiry lesson around the topic, this is a useful and flexible framework. In addition to viewing the Jewish experience in America through the broad lens of immigration, this resource also connects the Jewish experience with specific events across American history. One of the additional resources for instance, provides primary documents discussing the roles of Jews during the Civil War. Rather than a ready-to-go lesson, this resource is a great collection of the pieces needed for building lessons: background information, potential topics, inquiry questions, and links to primary sources. While the site links to many promising primary document collections, teachers will need to spend time identifying, selecting and modifying these documents. For additional information on adapting documents look to this guide. Use this essay to organize your thinking about Jewish Immigration or more specifically as the basis for a lecture or overview. For those teachers looking to teach this topic through documents, the essay includes key questions for students to explore using primary sources and links that make great starting points to find documents. And be sure to explore the other essays in this “Divining America: Religion in American History” series that offers more than thirty of these rich essays on key topics.

Puerto Rico Encyclopedia/Enciclopedia de Puerto Rico

Visitors to this site will find more than 1,000 images and dozens of videos about the history and culture of Puerto Rico. The work of dozens of scholars and contributors, the Puerto Rico Encyclopedia reflects the diverse nature of the island: a U.S. territory, a key location for trade in the Caribbean, a Spanish-speaking entity with its own distinct culture, and a part of a larger Atlantic world. Funded by an endowment from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Fundación Angel Ramos, the site is a key product from the Fundación Puertorriqueña de las Humanidades. It provides users with all content in both English and Spanish. Educators will find the site easy to navigate and conveniently categorized by themes; within each topic, appropriate subtopics provide an in-depth examination of Puerto Rican culture and history. Of particular interest to U.S. History teachers are the images and information found under History and Archeology. Here, teachers and students can explore a chronological narrative of the island's history and role at specific moments in U.S. and Atlantic history. Other sections worth exploring are Archeology (for its focus on Native American culture), Puerto Rican Diaspora (for its look at Puerto Ricans in the U.S.), and Government (for a detailed history on Puerto Rico's unique status as a free and associated US territory). Educators in other social science courses will also find valuable information related to music, population, health, education, and local government. In all, 15 sections and 71 subsections provide a thorough examination of Puerto Rico. The Puerto Rico Encyclopedia's bilingual presentation also makes it a good site for integrating Hispanic culture into the U.S. History curriculum, as well as helping to bridge curriculum for English Language Learners (ELLs) in the classroom.

Divided Allegiance

How can a person born in the U.S. to one U.S. citizen parent and one non-U.S. citizen parent (divided allegiance) be defined as a 'natural born citizen?'

Shouldn't a 'natural born citizen' be defined as being born with allegiance to the U.S. only?

Throughout the history of the United States, there has been a consistent evolution of who a citizen is and how a citizen is defined, as the United States Constitution has been both decided upon and modified on various occasions to expand the definition of who is a citizen and guarantee equal rights for all individuals. In the late 18th century, a citizen was defined as a white, male landowner, and African Americans could legally be held as slaves. The 1857 Dred Scott v Sandford Supreme Court case affirmed this definition. The Oyez Project (2005–2011) puts forth that in this case the Court found that "no person descended from an American slave had ever been a citizen." Six years subsequent to this decision, President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation, which declared "that all persons held as slaves within the rebellious states are, and henceforward shall be free."

This change was reflected in the Constitution of the United States in the 14th Amendment (1868), which states "All persons born or naturalized in the United States . . . are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside," as well as the 15th Amendment (1870), which puts forth that "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude." However, the next half century still saw roughly half of the country's population without full citizenship rights, as it was not until 1920 that the 19th Amendment was passed that granted women suffrage. To answer the particular question posed above, simply put, the 14th Amendment guarantees that a person born in the United States is thereby a citizen, even if both parents are illegal immigrants. However, this is not without controversy, and it has become a political issue, as citizens born to illegal immigrants have derisively been referred to as "anchor babies." For more on this issue, try searching the New York Times using the phrase "anchor babies." However, American children of foreign parents can be dual citizens depending in part on the rules of the other country. This status is conferred when "an individual is a citizen of two countries at the same time." The website newcitizen.us describes potential benefits to being a dual citizen; among them are "the privilege of voting in both countries, owning property in both countries, and having government health care in both countries." However, the U.S. Department of State puts forth that the U.S. government "does not encourage" dual citizenship "because of the problems it may cause," particularly that "claims of other countries on dual national U.S. citizens may conflict with U.S. law, and dual nationality may limit U.S. Government efforts to assist citizens abroad." To answer the initial question in regards to allegiance, allegiance may be more the way a person feels rather than actual law. On this topic the U.S. Department of State notes that "where a dual national is located [where the citizen resides] generally has a stronger claim to that person's allegiance."

Newcitizen.us. "Dual citizenship." 2011 (accessed on April 8, 2011).

U.S. Supreme Court Media. "Dred Scott v. Sandford," 60 U.S. 393 (1857). The Oyez Project (accessed on March 31, 2011).

U.S. Department of State. "US Department of State Services Dual Nationality" (accessed on April 8, 2011).

U.S. Immigration Support. "US Dual Citizenship." 2010 (accessed on April 8, 2011).

Divining America: Religion in American History

In this essay, authors Jonathan D. Sarna and Jonathan Golden of Brandeis University explore the impact Jewish immigration had on American history and culture.

Yes

Extensive bibliography provided.

Yes

Centerpiece is rich background essay.

No

Yes

Includes questions that require interpretation.

Yes

However, only yes if students read documents in the “additional resources” section.

Yes

Complex history succinctly explained for busy teachers.

No

No

Yes

Provides several entry points into a curriculum (e.g. this lesson could be part of a unit on immigration or the Civil War).

No

The Ways West

My ancestors migrated in the 1830s from Bradford County, Pennsylvania to Carroll County, Illinois. Is it likely that they used the Erie Canal and the Great Lakes to get there?

From the early 1830's, emigrants from rural northeastern Pennsylvania traveling to northwestern Illinois had two possible routes that were widely used. The most popular of these was to take the Erie Canal.

The first route: They would have loaded on a canal boat at Elmira, NY, just north of Bradford County, PA. From there they would have traveled on the Chemung Canal, completed in 1831. This would have taken them up to Watkins Glen at the southern tip of Seneca Lake. At the northern end of the lake in a portage called Geneva they would have picked up the Cayuga and Seneca Canal which was completed in 1830. This would have taken them up to the Erie Canal at Montezuma (near Cayuga), from where they would have traveled west along the Erie Canal to Buffalo. From Buffalo, they could have gone to Chicago via Lake Erie and Lake Michigan (a circuitous route of a thousand miles) on a steamboat. A route that could only be navigated when the lakes were not frozen over in the winter. After about 1833, another possibility was to get off the boat in Detroit (rather than Chicago) where they could have transferred their goods to a wagon or stagecoach which followed the Chicago Road. This path stretched from Detroit to Chicago across Michigan above its southern border and around the south of Lake Michigan.

From Chicago, if it was still the very beginning of the decade of the 1830s, they could have floated up the Chicago River and portaged over to the Des Plaines River on a short draft flatboat—or they could have followed the portage route by stage or wagon, depending on the seasonal water level—and from there they could have connected with the Illinois River and floated down to join the Mississippi at Grafton, IL, above St. Louis. From there, they could have taken a steamboat north along the Mississippi to Savanna, IL, in Jo Daviess (later called Carroll) County. However, by the middle of the 1830s, when many new settlers were pushing into Illinois to find farmland, they would almost certainly have taken another route from Chicago, which was the State Road that went more or less directly from Chicago, through Elgin and Rockford, IL, and then ended at Galena, in Jo Daviess County.

The second route: They could have floated down the Susquehanna River (or used the canal system that supplemented and paralleled the river) south to Harrisburg. They would then have transferred their goods to a Conestoga wagon or a stagecoach, and from there they would have turned west and traveled across south central Pennsylvania by way of the Pennsylvania Road (the Old State Road), which went from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh. At Pittsburgh, they would have transferred their goods to a boat and floated or steamed down the Ohio River to where it joined the Mississippi River at Cairo, IL. Then north by steamboat up the Mississippi to Savanna or Galena, IL (steamboats began regular service between St. Louis and Galena in 1827).

Another less probable route existed: Depending on how much they intended to bring with them, they might have considered whether it would be cheaper to travel with their goods to New York or Philadelphia—perhaps by way of the North Branch Canal or the Delaware and Hudson Canal and by toll road—and then to ship to New Orleans. From there to transfer it all to a steamboat bound up the Mississippi River as far as Galena. This may seem like a very roundabout way; however in the early 1830s shipping a lot of freight by road over the mountains of Pennsylvania and across Michigan and Illinois was more expensive than shipping it by water around the Eastern seaboard and up the Mississippi. The completion of the Erie Canal changed the calculation.

Their choice of route may have taken into account what they intended to carry with them, how much they could spend on their travel, as well as the local conditions along the various routes, insofar as they could foresee them. They would also have considered their strength and health, and whether they could endure pushing a stuck wagon over a mountain road or living in a makeshift tent on the upper deck of a steamship. If they were already farmers and planned on bringing livestock, tools, and household goods to the farmland of Illinois, that would have constrained their choices in a way that prospective miners, who also flocked to the region around Galena, did not experience simply because miners were not likely to have brought any of the tools of their livelihood with them when they moved. In planning their trip, they might have picked up a copy of Illinois pioneer and Baptist missionary John Mason Peck’s, Guide for Emigrants (1836), which recommended routes for prospective settlers from the East and even lists steamboat, stage, and canal fares. Also useful in planning their trip, if they were leaving in 1837 or later, would have been a copy of Samuel Mitchell’s, Illinois in 1837.

Gerard Koeppel, Bond of Union: Building the Erie Canal and the American Empire. Cambridge, Mass.: Da Capo Press, 2009. William J. Petersen, Steamboating on the Upper Mississippi. New York: Dover, 1995. 1st ed. published in 1937. The New York State Archives’ Erie Canal Time Machine.

John Mason Peck, A New Guide for Emigrants to the West: Containing Sketches of Michigan, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Missouri, Arkansas, with the Territory of Wisconsin and the Adjacent Parts. Boston: Gould, Kendall & Lincoln, 1836, pp. 371-381. Samuel Augustus Mitchell, Illinois in 1837; A Sketch Descriptive of the Situation, Boundaries, Face of the Country, Prominent Districts, Prairies, Rivers, Minerals, Animals, Agricultural Productions, Public Lands, Plans of Internal Improvement, Manufactures, &c of the State of Illinois. Philadelphia: S. Augustus Mitchell, 1837. Henry Wayland Hill, An Historical Review of Waterways and Canal Construction in New York State. Buffalo: Buffalo Historical Society, 1908, p. 150. Beverly Whitaker’s website, Early American Roads and Trails for information on the Pennsylvania Road and the Chicago and State Roads. W. B. Irwin, The Routes of Migration between the Atlantic Seaboard and the Midwest. Burbank: Southern California Genealogical Society, 1966.

Wisconsin State Historical Society Online Collections

Founded in 1846 and chartered in 1853, the Wisconsin State Historical Society is the oldest American historical society to receive continuous public funding. This website provides a host of online collections containing thousands of documents and images addressing Wisconsin's social, political, and cultural history, drawn from the Historical Society's collections.

Highlights include full-text access to 80 histories of Wisconsin counties, and 1,000 more articles, memoirs, interviews, and essays on Wisconsin history and archaeology first published between 1850 and 1920; thousands of articles from the Wisconsin Magazine of History; and hundreds of objects form the Society's Museum, including moccasins, dolls, quilts, ceramics, paintings, and children's clothing.

Other objects can be viewed at the website's Online Exhibits section, which includes objects from exhibits on Presidential elections, Wisconsin's Olympic speed skaters, the Milwaukee Braves, Jewish women, and family labor in Milwaukee after World War II.

The website also provides a vast collection of images available through Wisconsin Historical Images, including photographs, drawings, and prints relating to both regional history, as well as more national histories of 19th-century exploration, mass communications, and social action movements.